|

|

|

|

|

Adorazione

Perpetua |

|

|

|

|

|

Adorazione

Perpetua |

|

||

Miracle-working images

|

|

|

History The name refers to the hamlet of Romito (Hermitage) named after a small oratory, dedicated to Saint Lucy and built beneath the arches of a nearby Roman aqueduct. The remains of this oratory could still be seen in the 19th century. The mortuary previously sited by San Giuseppino moved to the chapel here in 1893, entrusted to Capuchin friars. The present church was designed by engineer Ezio Zalaffi in 1925, and became a parish church is 1929. It was damaged during WWII, and rebuilt in 1947 by another engineer, Galliano Boldrini. The portico was added in 1951 and the church consecrated in 1954.

|

History Also known as "the American Church". American Episcopalians in Florence held their first meetings in private homes and the British Embassy in 1846. When the Grand Duke of Tuscany was exiled in 1849, legislation was passed allowing non-Roman Catholic denominations. The first Episcopal services were hosted in 1853 in the church of Santa Maria del Carmine and the congregation of St. James was officially recognized in 1867. Construction of this church began on 23rd April 1908 and took three years, with consecration and the first service held in November, 1911. At this stage the campanile was incomplete, and work on it was only completed in 1927. The original architect was Riccardo Mazzanti, who was also responsible for the Palazzo Cesaroni on the corner of via della Scala. A major financial contributor was Pierpont Morgan, but his $10,000 came with strings. After looking at the architect’s drawings he declared the building inadequate and employed two architects of his own - Gino Marchi & R. Carrère - to make more elaborate plans. When these were agreed on he paid up. The church is English neo-gothic in style, with some fine stained glass. The large circular window in the façade depicts Christ's Entry into Jerusalem (1911) and was designed by Ezio Giovannozzi. The church was closed during World War II but suffered no damage and reopened in 1947. David Bowie married Iman here on the 6th of June 1992. Opening times For services or by arrangement in the morning. The church has a website. |

|

|

History

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

History This was the site of the 11th century Romanesque church of San Michele Berteldi, mentioned in a document dated 16th March 1055. This church had a single nave and an east/west orientation. It was later used by the Olivetan monks of San Miniato al Monte. The original church was demolished when the current Baroque church was built between 1604 and 1648 for the Theatine order. Amongst the families providing funding were the Medici - Cristina of Lorraine, wife of Ferdinando I, and her son Cardinal Carlo de' Medici particularly, the latter's name being on the façade. Renamed to San Gaetano (Saint Cajetan) in honour of Gaetano Thiene one of the founders of the Theatine order (and also the founder of the Ospedale degli Incurabili in Venice in 1522), but officially only after his canonisation in April 1671. Built to plans probably prepared by Father Anselmo Canigiani and Father Andrea Castaldo, founders of the Florentine community and Don Giovanni de' Medici, initially with help from Matteo Nigreti, who got the transept and choir finished by 1630. Then the nave was enlarged and the façade redesigned by Gherardo Silvani in 1648. The church was consecrated, whilst still lacking a façade, on the 29th of August 1649, with work continuing until 1701. Following the suppression of the Theatines in 1785 the church passed to the parish. In 2008 it passed to the Institute of Christ the King Sovereign Priest. The church The façade is made of of pietra forte, with ornamental detail by Alessandro Neri Malavisti. The statues in lower part date from 1686-1690 and are: San Gaetano Thiene over the left door, Hope and Poverty (seated either side of the arms of the Theatine order) over the central door - all by Balthasar Permoser, and Sant'Andrea Averlino over the right door, which is by Anton Francesco Andreozzi. The Medici arms and two angels over the central circular window are by Carlo Mencellini in 1692. He also enlarged the staircase in 1701. Interior The interior is a barrel-vaulted single nave, restrained baroque with stucco mostly by Giovanni Battista Foggini. The second chapel on the left, the Cappella Franceschi, has a large and frantic Martyrdom of Saint Lawrence of 1653 by Pietro da Cortona. The church now has framed printed guides in Italian to the art in each chapel, which helps identify Matteo Rosselli as being responsible for the better works here, including the altarpieces in the chapels either side of the apse, amongst some otherwise pretty nondescript 17th century stuff by the likes of Ottavio Vannini and Jacopo Vignali. Between the chapel arches in the nave is a cycle of over-life-size marble statues of Apostles and Evangelists. Below each are reliefs depicting episodes from their lives, mostly martyrdoms. The door to the left leads to the Antinori Oratory with three rare 12th-century Romanesque reliefs - Saints Michael, Peter and Miniato - from the original church of San Michele Berteldi. Also here is a silhouetted Crucifix with Saints Jerome, Mary Magdalene and Francis by Pesollino from c.1450, originally painted for the boys' confraternity of Sant'Antonio di Padova, called San Giorgio. It was recently restored for the Fra Angelico exhibition at the Palazzo Strozzi in 2025, revealing its superior quality. Miracle-working images Also in the Antinori Oratory is a Madonna which was on the exterior of the original church, facing the exit from a public bathhouse. This image was said to have closed its eyes in November 1506 in disgust because 'she did not want to see the sins that are committed there', probably male sodomy. This miracle lead to its becoming a place of veneration, despite the fact that many women would not come there due to its position opposite said bathhouse and the fact that the nearby streets and piazzas had the reputation of being rife with sexual crime. Update October 2025 The façade is currently covered in scaffolding, with rubble-catching panels. The original church of San Michele Berteldi, on the 16th-century Buonsignori Map. |

|

|

History The hospital here, dedicated to Santa Maria dell'Umiltà was founded in 1382 by Simone di Piero Vespucci. In 1400 Vespucci entrusted the hospital to the confraternity of the Bigallo and in in 1587 it was given to the mendicant Augustinian Hermit friars of San Giovanni di Dio by Grand Duke Ferdinando I. The complex was enlarged in Mannerist style from 1702-13 to designs, provided free of charge, by Carlo Marcellini. The Grand Duke provided the funds and houses belonging to the Vespucci where incorporated, including the birthplace of Amerigo. The church, which retained the name Santa Maria dell'Umiltà, was rebuilt at this time too, also to designs by Marcellini, with altars and monuments retained from the old church. The interior is a single rectangular nave with four side altars and reportedly unspecial. The dome was frescoed by Alessandro Gherardini initially, and in the late 17th-century by the Hungarian painter Giuseppe Dorffmeister. There is also an altarpiece by Alessandro Gherardini of The Virgin with Child and Saint Anne. In contrast the sweeping staircase of the Spedale vestibule next door, built in 1735 (see photo right) are splendid. The marble group on the landing is San Giovanni di Dio with Archangel Gabriel and a Poor Man Kneeling by Ticciati. The paintings and ceiling are by Vincenzo Meucci and Rinaldo Botti. The two fresco medallions on the walls, showing San Giovanni di Dio ministering to plague victims and giving bread to the poor, are by Violante Ferroni, a woman artist unusually commissioned to paint these large panels in the 1740s. These works are due to be restored in 1019/20. The order was suppressed in 1808 and the hospital passed into secular hands, although the entrance vestibule was used in the 19th century for masses for 'the convenience of the sick'. The hospital closed in 1982, moving to larger modern premises outside Florence. Gradually declining health service functions have lead to increasing disuse of the building. Opening times The church has been closed for years and the building left to crumble, with an 18th-century medallion falling off and shattering in 2015. |

||

|

History Founded here in 1323 as an oratory, the original church belonged to the Celestine monks, followers of San Pietro da Morrone, from 1327. (Peter of Morrone, who later became Pope Celestine V). In 1552 the Hospitaller nuns of Saint John of Jerusalem were installed here by Cosimo I and the Celestine monks were moved to San Michele Visdomini. During the 14th century the complex had housed "women of easy virtue" and was dedicated to St. Mary Magdalene. The nuns of the Knights of Malta (Cavilieresse strictly speaking) came here in 1552, from San Salvatore di Camaldoli in the Oltrano, and re-dedicated the church to Saint Nicholas of Bari, even though it is usually known as the church of Saint John the Baptist (or Saint John the Beheaded) the order's patron saint. Rebuilt by the nuns and reconsecrated in April 1553 with the current Baroque façade added in 1699. Suppressed in 1808 by Grand Duke Leopold, the church transferred to parish use in 1939 when architect Ezio Cerpi undertook restoration, with a view to returning it to its 16th century appearance. Interior It has an oddly huge entrance hall, with the original large cupboards, and inside a very tall nave with low aisles and plain square pillars dividing. The 14th-century interior remains largely unchanged. The first altar on the left has a poorly-illuminated Nativity by Bicci di Lorenzo, the father of Neri di Bicci, with too many angels (50!) The central altar on the left is very high-altarishly ornate. Above it is a Last Supper by Palma il Giovani, which is not bad, for him. Opposite it is a 19th-century della Robbia copy.

At the end of the aisles either side of the apse are two very worth-a-trip altarpieces

- a Coronation of the Virgin

by Neri di Bicci on the left (see above), with a fine and fascinating predella with

saints at either end and panels of The Beheading of St John the Baptist,

The Resurrection and a scene from the life of Saint Nicholas of Bari.

This altarpiece also contains a (relatively rare) fictive painted tabernacle. On the right is a sweet and architectural Annunciation by

the Master of the Castello Nativity. Both these works, date from the original 14th century

church of the Celestines. |

|

|

History The church was attached to the convent of San Giuliano, founded in the 14th century by Bartolo Benvenuti (who is buried here), consecrated in 1585 and suppressed in 1808. The convent is currently home to the Congregazione delle Figlie Povere di San Giuseppe Calasanzio, founded in 1889 by Mother Celestina Donati. Interior

|

||

History The Oratory of San Giuseppe, built in 1646, was part of the convent of the Montalve, the Handmaids of the Most Holy Virgin. The ceiling fresco here depicts Eleonora Ramirez de Montalvo Presents her Maids to the Virgin Mary (1717). Upon suppression in 1780 the Montalve moved to Sant'Agata in via San Gallo, then to San Jacopo in via della Scala, and finally to the Villa La Quiete in via di Boldrone.  |

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

History Originally consecrated on May 3rd 1206, the church belonged to the order of the Knights of the Holy Sepulchre, and from 1256 to the Knights Templar, later passing to the Knights of Malta. Building progressed through the 13th century, with a small military hospital added in 1311. The gothic portico is unusual, if not unique, in Florence, with the column capitals featuring carvings of the emblem of the Knights of Malta. The church was restored in the 17th century after falling into a poor state, when the large emblem featuring the cross of Malta was added. A convent was attached in the 18th century, but the complex was suppressed by Napoleon in 1808. The complex is now owned by the Scuola Lorenzo de' Medici, who have been responsible for recent restoration work and who use the church itself for conferences and receptions. It is also occasionally used for exhibitions. The interior Consists of a single nave, relatively unspoilt, with an altarpiece depicting The Mystic Marriage of Saint Catherine sometimes attributed to Ridolfo del Ghirlandaio. Also the impressive 16th century tomb of Luigi Tornabuoni (see right) nicknamed the Lion of Florence carved by Pierre de Aubisson, with bas-relief by an artist from Fiesole that Vasari called il Cecilia.

|

||

History In 1316 a Florentine carpenter called Cione di Lapo Pollini established Santa Maria della Scala, a hospital for the shelter of pilgrims and travellers. The silk guild of Por Santa Maria took over in 1351, by which time the hospital had also taken on the care of orphans. It was named for the Sienese hospital of the same name, with which it was linked. A loggia was added in the 14th century, the columns of which can still be seen on the exterior walls, together with the remains of the turning box on which abandoned infants were left, similar to the one at the Innocenti. In 1531, the hospital was suppressed and merged with the Innocenti. The church and convent were rebuilt in the 17th century when it was granted to the nuns of San Martino dalle Panche whose convent, near the Mugnone, had been destroyed during the siege. The interior acquired its current florid stucco work at this time, the work of Giovanni Martino Portogalli. The complex, which was henceforth known as the Monastero di San Martino a Mugnone, was occupied by the nuns until 1808, when the convent was suppressed. Since 1873 it has 'inconveniently', as one art historian put it, housed an institution for juvenile offenders. It now houses the Gian Paolo Meucci Penal Institute for Minors. Art highlights Reportedly an altarpiece of The Virgin and Child enthroned between Saints Sebastian and Martin by Ridolfo del Ghirlandaio. Also a Virgin and Child with Saints Julian and Sebastian (on first altar on the right) by the same artist, transferred here from San Pier Scheraggio in the early 19th century. It was described as being in a poor state in 1993. On a visit to Florence in April 2015 there was an enormous crane and considerable rebuilding going on. Lost art Botticelli's Annunciation fresco of 1481, now in the Uffizi, was taken from the church loggia here. It has recently had much restoration work done on it and is now properly displayed following the Botticelli room's recent (early 2017) rehang. (See before and after photos, below).

|

||

|

History This was originally a smaller church, hence the diminutive name, said by a plaque in the church to have been founded in 335 and consecrated in 404. The first actual documentary mention however is dated 30th October 1094, when the priest here is mentioned as having attended the consecration of Santa Maria Novella. By this time a larger church had been built and this church was itself refurbished in early Gothic style by the 13th century. By 1208 it was called San Paolino so as not to be confused with the church of San Paolo in the Ospedale dei Convalescenti nearby. Granted to the Dominicans in the 1217, who stayed here until 1221 (when they moved to Santa Maria Novella). Under Pope Leo X it became a parish church and passed to the Observant Franciscans in 1529. In 1618 it passed to the Carmelites with permission to build a convent. They refurbished the interior in 1621/2 rebuilt much larger in 1667, to designs by Giovanni Battista Balatri, when the church's orientation was rotated 90 degrees. This work was completed in 1693. Francesco Masini was responsible for the nave and Bastiano Messeri for the dome - the result was a baroquing up. The entrance gallery was built in 1779 to designs by Gioacchino Pronti from Rimini, who was then working on Santa Maria del Carmine after its fire and the façade of San Marco. It supports an organ by the Tronci brothers. Suppressed in 1810 and then in 1866 restored to the Carmelites who are still here. There was considerable restoration work undertaken in the 1970s. Façade The façade was never finished, only ever having a door and an oculus window. Over the door are the coats of arms of the Pope Leo X and Cardinal Giulio di Giuliano de' Medici, Archbishop of Florence and the future pope Clement VII. Interior A plain and nicely-proportioned interior with pale green-tinged walls. Two pairs of connected chapels in the nave and two more large altars in the shallow transepts. Also a lot of balconies, for some reason. The first chapel on the right as you enter is the most striking, with its pair of facing (Albizi family) tombs with emerging (carved) skeletons (see photo below right). There is a wood-panelled sacristy with paintings from the 18th century. Art highlights The second chapel in right nave contains the recently rediscovered Annunciation with Saints Peter and Paul by Ridolfo Ghirlandaio, previously attributed to 'a follower of Sogliani'. Much 18th century art by the likes of Vincenzo Meucci (The Marriage of the Virgin), Giovanni Domenico Ferretti (The Agony of St Joseph), Francesco Curradi (The Rapture of St Paul), Ignazio Hugford and Gherardini. Lost art There is panel depicting Saint Paul by Bernardo Daddi, dated 1333 and now in Washington, thought to have come from this church or the Ospedale di San Paulo nearby. Local boy Sandro Botticelli's serious and impressive high altarpiece Lamentation (see below) of c.1490/95 is now in the Alte Pinakotek in Munich. It was installed in an elaborate architectural frame with doors, and was commissioned by Frosino di Cristofano Masini, the prior here from 1412-1451, who was buried in front of the high altar. A guidebook of 1860 mentions an Annunciation attributed to Fra Angelico, which might conceivably be the one mentioned above by Ridolfo Ghirlandaio.

Notable locals

|

|

|

Lost art Giovanni Bizzelli's Virgin in Glory with Saints (see right) is in the Andrea del Sarto Cenacolo Museum at San Salvi.

|

||

|

Opening times

The Cenacolo is open daily 8.15-13.50

Bibliography |

|

|

|

History Named for the obscure saint Honofrius and called di Fuligno after the Franciscan nuns from Foligno who lived here from 1419. The complex had originally, from 1316, been occupied by Augustinian nuns. It was rebuilt and consecrated in 1429. The complex was suppressed in the 19th century, the remaining Franciscans being moved to Sant'Ambrogio, with the buildings then used as a girls' school, to prevent them having to resort to begging, 'a violation to common decency'. The refectory was sold separately, though, being used for the manufacture of silk and the painting of carriages. The discovery of the Last Supper fresco there in 1843 began the process of repair leading to it being opened to the public. It housed the Egyptian Museum for a while, and then the Feroni collection of pictures. Closure from the Second World War through to the flood of 1966 led to the rooms being used to store flood-damaged works, until their reopening in 1990. The Cenacolo The Cenacolo (Last Supper) fresco is to be found in the refectory, through the open doors in the old convent building to the right of the church. This lunette-shaped fresco is by Pietro Perugino, but was previously thought to have been an early work by Raphael (hence the bust of him on display here), this attribution having been based on a half-deciphered inscription on the robe of Saint Thomas in the fresco, and there's still some argument over whether it might have had more than its share of input from Perugino's pupils, of which there were many, including Pinturicchio. It was painted 1480-85 and the scene of The Agony in the Garden seen in the background is the following scene in Christ's Passion and also reflects the fresco of 1462 by Neri di Bicci which this work replaced, presumably as the Neri fresco was thought to have become old fashioned. (Confusingly when this Last Supper was thought to be by Raphael counter claims attributed it to Neri di Bicci, presumably because of the existence of documents relating to the previous fresco.) The fictive stone framing has small roundels containing portraits of Franciscan saints. The two rows of six columns which frame the Agony are said to relate to the Apostles having been described as the pillars of Christianity. There are 33 cenacoli in the refectories of central Florence, and this is one of the best. There are other works on display too, including Perugino's fine Crucifix with the Virgin and Saints from the demolished church and convent of San Girolamo delle Poverine. Several by Ridolfo del Ghirlandaio, including a Raphaelesque Virgin and Child which was originally in the convent of the Murate. A Mystic Marriage of St Catherine by Antonio del Ceraiolo, a pupil of Ridolfo Ghirlandaio and then Lorenzo di Credi, which was originally in the church of Santa Lucia. (Also one in the Bombeni chapel in S.Trinita?) The Assumption of the Virgin by Valerio Marucelli, in the entrance antechamber, was originally over the high altar in the church here.  There

are also a few works by Lorenzo di Credi, including very nice bits

of an altarpiece from the convent of San Gaggio and a portrait of a youth.

This portrait was stolen by German soldiers in 1944 and recovered in 1963.

There are those who think that it's a self portrait, and those who don't. There

are also a few works by Lorenzo di Credi, including very nice bits

of an altarpiece from the convent of San Gaggio and a portrait of a youth.

This portrait was stolen by German soldiers in 1944 and recovered in 1963.

There are those who think that it's a self portrait, and those who don't.My faves here, though, are six altarpiece panels by Antonio Rimpatta (see right). I'd never heard of him either, but his faces are winningly serene whilst still very human and very Flemish-influenced. The Mormile Polyptych that they are taken from, originally in Milan, was illegally dismembered, sold and exported. Later these parts were recovered, minus the frame and, it is thought, some panels. Also here are some detached frescoes by Bicci di Lorenzo. A tabernacle of The Virgin and Child with Saints by Giovanni da San Giovanni, formerly on the wall of the suppressed convent of Sant'Antonio in via Cennini, has been set up beside the entrance. Opening times The Cenacolo is open Tuesday, Thursday and Saturday, 9.00 - 13.00

Bibliography |

|

|

History A convent founded in 1309 as a satellite of San Lorenzo. The building was completed in 1327 and settled by Benedictine nuns until 1435 when it was taken over by Franciscans. There were two churches within the complex, the second built in the mid-16th century, at the same time as the first was rebuilt to accommodate counter-reformation innovations. Suppressed at the beginning of the nineteenth century and by 1810, after renovations by architect Bartolomeo Silvestri, it had became a tobacco factory. The building later housed a centre for the care of the evicted and then classrooms and offices of the University of Florence. In the 1980s it was bought by the State in order to create a barracks for the Guardia di Finanza. Work began in 1985 but was later abandoned. The complex was left enclosed in a cage of scaffolding and sheeting and became a victim of bureaucracy. Meanwhile the surrounding area descended into squalor, criminality, and drug dealing. In 2004 the Region of Tuscany signed an agreement for Sant'Orsola to become an extension to the Central Market and the headquarters of the District Directorate of Customs of Florence. But then all that happened was the scaffolding coming down, in 2007.  The same year saw research published suggesting that in 1542 Lisa Gherardini, the (recently confirmed) subject of Leonardo's Mona Lisa, was buried in the church of the convent of Sant'Orsola, where she had spent the last years of her life, following the death of her husband, with one of her daughters, Marietta (Sister Ludovica). The gutting of the building in 1985 would have removed any traces of tombs or bodies, but the architect from the time says that there was nothing but 'devastation' within the shell of the building by that time anyway. This didn't stop excavations beneath the concrete laid in the 1980s and two bodies being found, in 2011 and 2012, and claims being made that they were the bones of Mona Lisa. Both of them were found not to be. The most recent admission of failure by the somewhat publicity-led team being in September 2012. A film about the digging is here. In recent years many renovation plans and initiatives have been announced. The building has also had to suffer 'edgy' art and 'sound installations'. More recently plans announced in August 2017, including the creation of the Monnalisa restaurant and museum and the Bocelli Academy Music School, came to nothing. Lost art A panel of The Arrival of Saint Ursula at Cologne from an altarpiece by Bernardo Daddi (see right) is in the Getty Museum. Update January 2021 Many have been the announcements of development projects, for many years, all coming to nothing. Now comes news of a French developer called Artea and a 31.5 million euro restoration aiming to turn the ruined complex into a community centre. Work is expected to begin in 2022 and be completed by 2025. We'll see. Update 14th August 2022 The above process seems to be progressing! Città di Firenze have today reported that 'the facades, coverings and restoration of ancient capitals and frescoes have been completed' and that the handover to Artea is expected next month and the fitting out of the interior should follow. All the usual spaces are promised: schools, workspaces, a library, accommodation, courtyards, gardens and 'a museum that will trace the history of Sant’Orsola through the centuries'. Update October 2024 An expected opening in 2026 is reported |

||

|

Santa Caterina |

||

History Founded by Augustinian nuns in 1310 and belonging to the Canons of the Duomo. The monastery, located to the right of the church, was enlarged during the next two centuries. The wheel, the symbol of Saint Catherine's martyrdom can still be seen on many nearby houses. In the 16th century the sisters were moved and the monastery, by now known as Santa Caterina al Magnone, passed through various orders, including the Humiliati, the Franciscans and the Cavalieri di Santo Stefano, later becoming the responsibility of the Company of the Bigallo. In 1615 the complex became a home for abandoned girls, then with secularisation under Peter Leopold in 1778 it became a school for 'poor spinsters' and later a salt and tobacco warehouse. Following a plan by Gaetano Baccani failing due to financial difficulties, and the fact that his single nave church was deemed too small, the church was rebuilt in current neoclassical style by Giuseppi Martelli from 1858. The façade remains unfinished, though. and very odd looking - the plan was for a triple-arched loggia. The church was opened on 31st December 1863. Interior An oddly monumental interior with eight pietra serena columns (recycled from the Baccani plan) dividing a wide barrel-vaulted nave from its diminutive aisles. A rich decorative scheme was planned but never carried out. |

||

|

History First called Santa Lucia a Sant'Eusebio, after a nearby leper colony, and a parish church by 1221, the church was later called Saint Lucia sul Prato after the expanse of grass that fronted it. The chapel here was first mentioned in documents whan it was granted to the Umiliati order in 1251 by the bishop of Florence, Giovanni de’ Mangiadori, because, as at the monastery of the Ognissanti nearby, they needed proximity to the Arno for wool-working purposes. They sold the church to Cosimo I for 840 scudi and so in 1547 it passed to Augustinians from San Donato a Scopeto by the Porta Romana (called the Scopetini), who had had their convent destroyed so as not to provide refuge for the attackers during the siege of Florence in 1529-30. This order spent the years following their acquisition restoring the church. Following the Augustinians' move to San Jacopo sopr'Arno the complex was taken over by the fathers of San Vincenzo de 'Paoli in 1703 and then in 1720 it was entrusted to secular clergy. Its current neoclassical appearance results from subsequent rebuilding between 1838 and 1885. This work gave us the façade by John Mannaioni, the ceiling painting and the bas reliefs in the apse. The flood of 1966 resulted in the loss of baroque side altars, the marble balustrade between the apse and the knave, and the original floor. To the left of the church was the house of the Company of the Blessed Sacrament, where silk weaver Ippolito Galantini (1565-1619) first began to instruct children in Christian doctrine, before founding the confraternity of the Vanchetoni in San Francesco dei Vanchetoni. He is depicted in a fresco behind the high altar here. Interior It's aisleless, compact and squarish inside, pale with some quite chunky pietra serena detailing. Three arches along each side, both sides consisting of a pair of recesses with a chapel at the apse end.  The

facing pair of recesses nearest the door each contain a damaged fresco

fragment. The one on the left is a fine and unusually relaxed Annunciation

(see right). It's late 14th century and in composition and

positioning it emulates the famed miracle-working Annunciation at

Santissima Annunziata, with some

claims that it might even predate it. Previously anonymous it

has, following restoration in 2013, now been ascribed to Nardo di Cione. The

facing pair of recesses nearest the door each contain a damaged fresco

fragment. The one on the left is a fine and unusually relaxed Annunciation

(see right). It's late 14th century and in composition and

positioning it emulates the famed miracle-working Annunciation at

Santissima Annunziata, with some

claims that it might even predate it. Previously anonymous it

has, following restoration in 2013, now been ascribed to Nardo di Cione. The recess on the right contains the bottom half of an even more damaged fresco of The Baptism of Christ (see photo below right), painted by Angelo La Naia in the 1950. This recess contained the baptismal font until a new font was installed in the left aisle in memory of a young man of the parish executed by the fascists for refusing to enlist. The fresco was covered over at this time until a few years ago when the damp caused the cardboard covering to warp and come away. Now proper restoration is being considered. The middle recess on the right contains a fresco from 1984 by Luciano Guarnieri, a pupil of Annigoni, depicting The Crucifixion. Some of the figures are portraits of locals, including a nearby butcher; and one of them (the man in the brown jacket at the foot of the cross) is Giuseppe Prezzolini, the writer and journalist. There's also a square painting here of The Adoration of the Shepherds by a previously unidentified, said to be northern, artist, He was known as the Master of Santa Lucia sul Prato and it was said that he may have been attached to Ghirlandaio's workshop. After recent cleaning for an exhibition, however, a name has been given to its painter: Alexander Formoser, a painter sent to Florence by the Hungarian King Matthias Corvinus, to learn the Florentine way with art. The painting certainly shows the influence of Ghirlandaio's version of the same subject in Santa Trinita. The square apse has long carved relief panels on the sides in plaster by Salvatore Bongiovanni, depicting Moses quenching the Jewish people and Moses saving the Jewish people from snakes. There's a painting of the crucifixion on the wall behind, but with the actual crucifix is carved and is from the Company of San Benedetto Bianco and dates to the 16th century. Flanking this on the back wall are saints with children - Santa Lucia and Sant'Ippolitto Galanti, painted in the 1950s by Angelo La Naia and now pretty grubby. There's an organ gallery (and organ) on the inner facade and a murky circular ceiling painting. Patterned stained glass windows over each side arch help the light and calm and Brunelleschi-type cube effect. The ceiling painting is Saint Lucy Brought to Heaven by Angels, painted by Paolo Sarti between 1831 and 1838. Lost art This church is the most likely original location of an altarpiece by Fra Angelico of c.1427/8, of which only the five predella panels remain. Saint James the Great Freeing the Magician Hermogenes is in Fort Worth Texas, The Naming of Saint John the Baptist is in the San Marco Museum, The Dormition of the Virgin is in Philadelphia, The Meeting of Saints Dominic and Francis is in San Francisco, and The Vision of Saint Lucy is in the Feigen collection. Its possible placing here is down to an 18th-century inscription on the back of one panel mentioning the Ognissanti, a church which this one depended on, and the presence of Saint Lucy. The lost Bianchi crucifix A crucifix kept in the Cappella di San Benedetto on the left-hand side of the church, which was (and still is) used for meetings and film shows, was consigned to storage around 1920 and forgotten. It was found in 2010 and was found to be, behind it's more modern front, an original Bianchi cross carried in their processions and mentioned by many sources, including Richa. When it was given to the church two members of the group donating the crucifix were said to have had their sight miraculously restored after having been blind for some time, Santa Lucia being the saint who protects eyesight. It turned out that when it was put in the chapel a second larger wooden cross was applied and attached with iron latches. An invoice from around 1710, for making the larger cross and the latches, was found, so proving the pre-existence of the crucifix before 1710. It has been restored and was returned to the church in June 2013. There's a video news report here. Opening times 9.00 to 12.00, 5.00 to 6.30 (Mass at 6.00) Sundays 8.30 to 1.00 (Masses at 9.00, 10.30, 12.00) |

|

|

|

||

|

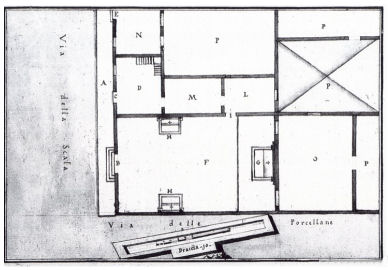

The false-stone facade's doorway is surmounted by a glazed terracotta

lunette (see above) said to be by Giovanni della Robbia, the

grandnephew of Luca, whose work is usually in deeper relief and with more

colours than his granduncle's. It depicts John the Baptist and two darkly robed and hooded members of the

confraternity, with whips. The doorway leads to the entrance hall and

cloister, the only two rooms of the late-15th-century construction which

remain. A member of the confraternity, an architect called Alfonso Parigi

the Elder drew a map of the rooms (see below right). The ingresso

(entrance hall)

and cloister are at the bottom. A walled-up doorway at the end of the

cloister once led to an office/changing room and beyond this was the

oratory, which is now a post office. Lost art |

|

|

|

|

||