|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Badìa Fiorentina |

||

|

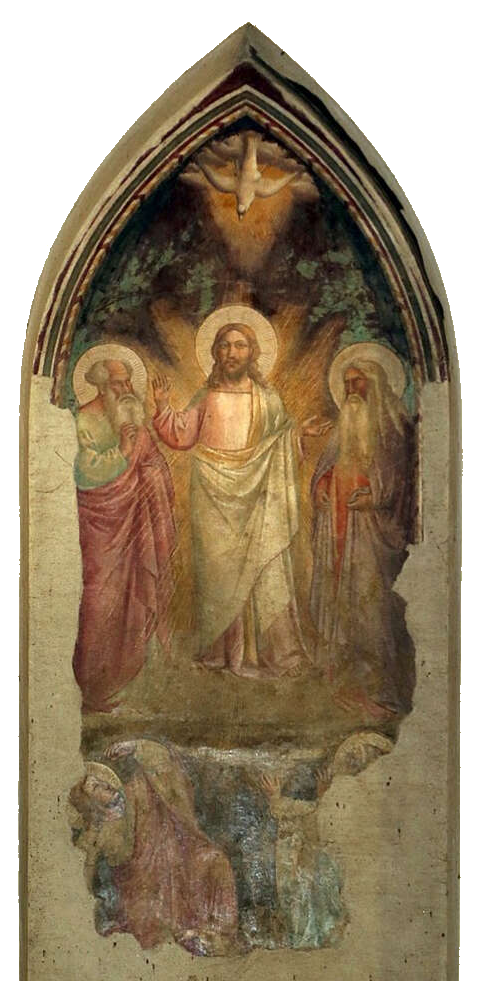

History The Benedictine abbey here was founded and endowed in 978 by Willa, the widow of Hubert, Margrave of Tuscia (Tuscany), then a province of the Frankish empire, in his memory. The church here, dedicated to Santo Stefano, was enlarged in 1284-1310, probably by Arnolfo di Cambio, then entirely rebuilt in 1627, to a plan by Matteo Segaloni, with the consequent destruction of frescos by Giotto and Masaccio and the rotation of the church's axis through 90°. Currently the church belongs to the Fraternity of Jerusalem, a French monastic order founded in the 1970s. The church There is no real façade (see right), but the entrance portal in via del Proconsolo (like the entrance from via Dante Alighieri) is by Benedetto da Rovezzano (1495) and incorporates the dolphin motif, the emblem of the Pandolfini family who were considerable benefactors of the church. The enamelled terracotta Virgin and Child in the lunette is by Benedetto Buglioni, who set up a rival studio to the della Robbia family and probably trained with them. Vasari's story that the trade secrets were leaked to Buglioni by a female employee of the della Robbia is probably an invention. Both entrances lead into a small cloister around which you'll find the door to the Pandolfini chapel (which I've never found open) and the ticket office/shop in the 16th century Bonsi chapel. Interior A very tall Greek cross shaped church, the interior dating from the rebuilding of 1627-31, with the carved wooden ceiling by Felice Gamberai also dating from this time. On the left as you enter is the sweet art highlight Filippino Lippi's Vision of Saint Bernard, an altarpiece originally painted for the del Pugliese family chapel in Santa Maria delle Campora between 1482 and 1486 (that's Piero del Pugliese, a wealthy wool merchant, in the bottom right hand corner), a Dominican church that was outside the city walls and was destroyed before the siege of 1529/30. It was brought it when the church was demolished and has been here since. It's an early work by Filippino so still shows the influence of Botticelli, his teacher. The Vision... is an episode from Bernard's life popular in Florence but rare elsewhere in the main field of altarpieces. The carved altarpiece opposite (The Virgin between Saints Leonard and Lawrence) and the two delicate red-backed tombs in the transept are admirable works by Mina di Fiesole. The one in the left transept is the memorial to Countess Willa's son, the revered Hugo, Margrave of Tuscany, who carried on his mother's habit of generous endowment. On the inner façade, above the door, are fragments of late 14th century fresco panels, with baroque fake-architectural embellishments. Opposite the organ, over the choir loft, which is over Hugo's tomb, (see right) is a good Assumption and Two Saints by Vasari. Good being the most we can expect from him. To the left of it, in the chapel behind the Filippino Lippi (called the Saint Bernard Chapel from when the Lippi used to be here) are detached frescoes from the previous church by someone in the circle of Nardo di Cione. They depict scenes from Christ's Passion, including a dramatic Hanging of Judas.  The large baroque chapel under the organ has 18th century ceiling frescoes by Vincenzo Meucci and Pietro Anderlini celebrating the life of Maurius, an obscure Benedictine saint. The chapel to the left of the apse has a Way to Calvary by Giovanni Battista Naldini which has some mannerist charm. The choir has large and pale, but impressive and interesting, trompe l'oeil architectural frescoes of 1734 by Giovanni Domenico Ferretti (see below right). The Crucifix hanging over the sanctuary here is a modern work imitating the Byzantine, as are the icons either side. The walnut stalls, with their intarsia, and the lectern too, were made in 1501-02 by Francesco and Marco del Tasso. A small fresco of the Transfiguration by Taddeo Gaddi from the late 1340s was discovered (see photo right) behind a brick wall and detached in 1967, during restoration work after the 1966 flood. It's sinopia was also found and detached but neither is currently on display. The Cloister of the Oranges Built in 1432/38, to a design by Bernardo Rossellino, this cloister is a treat of still-vivid outdoor frescoes, on the upper level, depicting the life of St Benedict. They are by an unknown master, and they deserve to be much better known. There is one theory that attributes then to the Portuguese painter Giovanni di Consalvo, a follower of Fra Angelico, because the abbot here at the time was Portuguese. Some claim that they are more likely the work of Zanobi di Benedetto Strozzi another follower of Fra Angelico. You'll be reminded of Masaccio and they were painted in the decade following his death. The second scene (see far below) shows one of St Benedict's earliest miracles when, as a boy, he fixed his nurse's broken sieve with prayer. The right-hand scene shows the sieve hung over the church door to be venerated. The fourth scene, though, of the saint throwing himself into thorn bushes to resist temptation, was painted by Bronzino a hundred years later, and is in far worse condition. After seven more scenes of monk-related miracles the two faded scenes in the corner opposite the entrance are by a lesser hand, and then there are six sinopie found during restoration work.

The Pandolfini Chapel

Lost art |

|

|

|

|

||

|

Bigallo |

||

History This one-bay loggia and two-bay oratory was built between 1352 and 1358, on the site of the tower of the palazzo of the Adimari family, destroyed in 1248 following their banishment for their Guelph leanings. It was built as an expansion of the headquarters of the Compagnia di S. Maria della Misericordi, originally built in 1321-22, by the architect and sculptor Alberto Arnoldi, who also worked on the Duomo, carving some of the bas-reliefs on Giotto's campanile. The sculptures in the niches on the façade - a Virgin and Child in the centre with Saints Peter Martyr and Lucy flanking - are also his work. The Confraternity of the Misericordia was established to help those in needy, the sick and prisoners and to bury paupers. They shared the complex with the Compagnia Maggiore di Santa Maria del Bigallo when the merged in 1425, and continued to do so after their seperation in 1489. The Misericordia left the Bigallo thirty-five years later finally settling across the road in 1576. Art highlights Devotional triptych of the Virgin and Child Enthroned by Bernardo Daddi. A Crucifix from c.1230 by the Master of the Bigallo Crucifix is early enough for him to be presented as triumphant, not suffering. There's an anonymous fresco here of the Madonna della Misericordia from 1342 which features the earliest known view of Florence. A 14th-century fresco by Niccolò di Pietro Gerini (with Ambrogio di Baldese) showing the orphan-homing activities of the Misericordia brotherhood, originally on the exterior wall, now taken inside. Frescoes of twelve episodes from the life of Tobias from the second half of the 14th century by an anonymous master. Also a 15th-century Virgin and Child by Domenico di Michelino, the pupil of Fra Angelico who also painted The Comedy Illuminating Florence, the famous fresco depicting Dante in the Duomo. Lost art An Annunciation dated 1380 by Agnolo Gaddi, now lost. An altarpiece of the Virgin and Child with Saints Peter Martyr and John the Baptist (see right) painted by Mariotto di Nardo (the son of Nardo di Cione) in 1416 was stolen before 1920. We only have the black and white photo to show its original state, but the three main panels did quite recently appear at the Florentine dealers Moretti. Photos at the bottom of this page. Opening times |

||

|

Duomo |

||

|

Opening times:

A 19th-century photo of the

bare façade |

Santa Reparata

This small Romanesque cathedral, possibly 6th-century, had the current

Duomo built over it - its remains are to be seen in a crypt under the west end.

It had a raised presbytery above a crypt and the bishop and canons sat behind

the high altar and thereby could look at the reverse of the workshop-of-Giotto

altarpiece, mentioned and pictured above left.

|

|

|

|

||

|

Cristiana

Evangelica |

||

|

|

Acquired in 1879 by Count Piero Guicciardini. His collaborator was Theodoric Pietrocola Rossetti, who influenced the Gothic Tuscan style of the building. He was a cousin of the father of the pre-Raphaelite painter Dante Gabriel Rossetti.

|

|

|

Misericordia |

||

History The Confraternity of the Misericordia was established to help those in need, which in the medieval period usually meant plague victims, hence Saint Sebastian being their patron saint, along with Tobias, for their other dedication, to the burying of the poor. They were founded in 1244 by Saint Peter Martyr, from Verona. They originally used the Loggia del Bigallo, sharing it with the Compagnia del Bigallo from 1425, moving to this building in 1576. Now the institution provides wider-ranging social and medical help, still staffed by volunteers. Interior It's long and low and not bright, being all pietra serena above and dark wooden stalls below. A pair of small stone side altars face each other two thirds of the way down. The ceiling is dark wood too, flat with gilded coffers. There's an Andrea della Robbia altarpiece, which had been commissioned by Francesco Sassetti for his chapel in the Badia Fiorentina, and a marble Saint Sebastian (the Brotherhood's patron saint) by Benedetto da Maiano. The church in art The entrance to the Misericordia as it was then is to the left of a late 19th century painting by Fabio Borbottoni of the Canonica del Duomo. The museum Reopened in 2016. It's all very modern, with sparse displays and a few videos, through fourteen small rooms of art, manuscripts and divers strange items related to the order's job of helping the sick and needy and disposing of their bodies, whilst wearing spooky pointy hoods with eye holes cut out, the better to retain their anonymity. The entrance is in the shadow of Giotto's tower, behind the ambulances, through some glass doors and up in a lift to the 4th floor, so there are fine views towards the tower and the Baptistery. It is open Monday–Friday 10.00 – 12.00 and 3.00–5.00; Saturday 10.00 –12.00. Entrance is free, but donations are welcome, in a discrete glass box as you leave.

|

|

|

|

Orsanmichele |

||

|

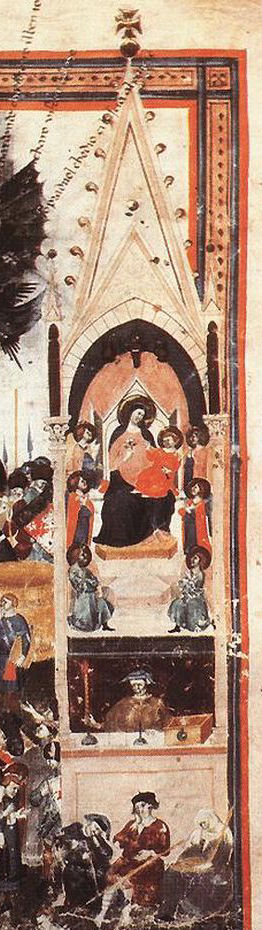

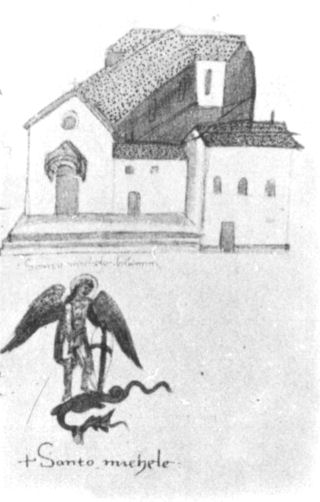

History  The name derives from the Lombard church of San Michele in Orto (Saint Michael in the Garden) which had burned down in 1239 and on the site of which the Commune ordered the building in 1249 of a piazza with a grain and corn market, for which Arnolfo di Cambio built a loggia in the late 1280s. (This loggia took up much less of the Piazza di Or San Michele than the current building, which fills it.) Upon one of the pilasters in this loggia a frescoed image of the Virgin was painted (with Saint Michael on another) and in 1292 it started working miraculous cures, according to Villani's Chronicle. A company of laymen was formed, the Laudesi of Our Lady of Or San Michele and the offerings left were distributed by the company to the needy. The Franciscans and the Dominicans reportedly became jealous of these town-centre miracles as they languished in Florence's outskirts. A factional feud, involving the Black Party, resulted in the burning down of the city centre, including Orsanmichele, on June 10, 1304. This also caused the destruction of the original image of the Virgin, which was swiftly replaced by a new image, with no interruption to the miraculous cures and resultant donations. This image is presumably the one shown in one of the miniatures in the Biadaiolo codex of 1340 (see right). In 1336 the Signoria granted the silk guild permission for a new building, to replace the temporary structure built after the fire. It was to be half oratory and half corn market, with a granary and offices on the upper floors, and building commenced the following year, supervised by maybe Francesco Talenti or maybe Andrea Pisano. Or maybe Neri di Fioraventi and Benci di Cionne, who later went on to build the church of San Carlo dei Lombardi opposite. The grain trade guilds were passed over for this plum building work as they had much less power and political clout. That a granary should have been placed so centrally reflects the importance of such a market in times of regular famine. The larger guilds were made responsible for the external decoration, including the now-famous statues filling the fourteen niches, and the inside was entrusted to the Laudesi, where each of the twenty-one guilds were given a pilaster to fresco. Work was completed in 1347, in the same year that a new version of the miraculous Madonna was painted by Bernardo Daddi, even though the previous replica was said to have still been in good condition, it is said to have been failing in the miracle-working  department. (The Virgin and Child in the Oratorio di Santa Maria in Pian di

Mugnone, north of Fiesole (see b&w photo

right) is believed to be this disappointing painting. In 1349 the Laudesi employed Orcagna

(Andrea di Cione) to lavishly enclose this painting. He finished

the spectacular marble tabernacle in 1359 and the railing by Pietro di Migliore was

completed in 1366. The corn market was moved in 1367, following complaints that

the dust and noise were not conducive, to the Piazza del Grano and in 1382 the filling in

of the arcades took away the last traces of the appearance of a loggia and the

building fully became a guild church. The windows are the work

of Simone di Francesco Talentini and were installed within the arches in the

last decades of the 14th century, with stained glass by Franco Sacchetti.

department. (The Virgin and Child in the Oratorio di Santa Maria in Pian di

Mugnone, north of Fiesole (see b&w photo

right) is believed to be this disappointing painting. In 1349 the Laudesi employed Orcagna

(Andrea di Cione) to lavishly enclose this painting. He finished

the spectacular marble tabernacle in 1359 and the railing by Pietro di Migliore was

completed in 1366. The corn market was moved in 1367, following complaints that

the dust and noise were not conducive, to the Piazza del Grano and in 1382 the filling in

of the arcades took away the last traces of the appearance of a loggia and the

building fully became a guild church. The windows are the work

of Simone di Francesco Talentini and were installed within the arches in the

last decades of the 14th century, with stained glass by Franco Sacchetti.

Interior

Miraculous images

The third image cult related to the Madonna

della Rosa, a marble sculpture of the Virgin and Child which has been

attributed to Niccolò di Pietro Lamberti. Veneration followed desecration in

1493, when the face of the Virgin and the eyes of the Child were attacked with a

knife by a Jewish boy, so the story goes, who went on to attack images of the

Virgin in

Sant'Onofrio and

Santa Maria in Campo, neither church being

nearby exactly. The boy was caught and confessed under

torture. In punishment his eyes were gouged out before the Madonna della Rosa

and his hands cut off before the other two desecrated images. He was then stoned

to death in Piazza Santa Croce. An inscription beneath the statue, still in Orsanmichele, commemorates this event. Later investigations have found no traces

of scratches. |

|

|

|

San Carlo dei Lombardi |

||

|

History Originally a chapel dedicated to St Anne, then the church of San Michele, and now called San Carlo, this church was built at the expense of the Company of the Laudesi to provide the consecrated altar not yet present in their grain market/tabernacle of Orsanmichele opposite. It was built 1349 to 1352 by Neri di Fioraventi and Benci di Cione at the same time as Orcagna's new tabernacle in Orsanmichele. This pair had worked on the rebuilding of Orsanmichele in 1337 and later went on to supervise new projects at the Duomo between 1365 and 1367. The work here was continued by Simone di Francesco Talentini (who was responsible for the carved windows of Orsanmichele) late in the 14th century and this complete rebuilding was completed in 1404. The dedication to San Michele took place at this time. As the influence of the company of Orsanmichele waned the church was taken over in 1616 by the company of San Carlo of Lombardi (Charles Borromeo) who changed the church's dedication. Interior Tall and square and plain with worn 15th-century fresco decoration, found in 2006 during restoration work, and scenes from The Life of San Carlo Borromeo in the lunettes on the walls of the wings of the three-part presbytery, which were restored in 2005. Below on the left wall is San Carlo Borromeo in Glory (1616) by Matteo Rosselli and on the right is a Presentation at the Temple by Fabrizio Boschi of similar date. There are various bit of modern sculpture and fittings installed during the 2005/6 work, along with the glass entrance porch. On the right wall there's a wooden polychrome Crucifix by Orcagna of c.1360. This crucifix was formerly in Orsanmichele opposite, where a miraculous cult sprang up around it in the mid-15th century.  Niccolo di Pietro Gerini's Entombment and Resurrection of Christ of c. 1385/90, returned from restoration in 2015 and looking fine back over the high altar. The church in art Appears to the right in a late 19th century painting by Fabio Borbottoni called Veduta della via di Calzajoli avanti il 1844.

|

|

|

|

San Firenze/San Filippo Neri |

||

History San Florenzio was a 12th-century Romanesque brick church when the Oratorians acquired it in the 1640s. A new church was commissioned to plans from Pier Francesco Silvani, after initial plans, commissioned from Pietro da Cortona, were found to be too extravagant. The church's façade, said to have been inspired by San Gaetano, was finished by Ferdinando Ruggieri in 1715. The separate oratory was demolished and rebuilt to designs by Zenobi del Rosso from 1772-5 who then designed and built the unifying facade with the matching oratory entrance at the right end. The seminary between the oratory and the church was suppressed in 1769 and again in 1808, but was returned to the Oratorians in 1814. When Florence was the capital of Italy, around 1866, the complex (except the church) was used as government offices. Later it was put to use as civil law courts, amongst other things, and since July 2017 it has housed the Franco Zeffirelli International Centre for Performing Arts. On the 24th of January 2021 the Andrea Bocelli Foundation ceremoniously opened its new HQ and education hub here too. Interior  The space is big, tall and baroque but with no aisles, just three huge altars down each side, each with big altarpieces by 18th century painters you won't have heard of. It's all dark pietra serena with a flat and very gilded coffered ceiling, with a central ceiling painting by Giovanni Camillo Sagrestini depicting the Glory of St Phillip, under an airy clerestory with four plain windows down each side. There's a stone organ gallery above the door. The semi-circular apse has a painted half-dome frescoed with The Trinity, Apostles and Florentine Saints by Niccolò Lapi. There are two confessionals between the altars on the left, and two more at the back. There's only one on the right as where another should be (between the second and third altars) is the entrance to a chapel. This space (see right) is wider than it is deep, with a carved altarpiece, some more dark art, and two more confessionals. Filippo Neri was famously a keen hearer of confessions. In this chapel you'll also find a chair, a small table and the death mask of Filippo Neri in an ornate glass case with his bust on top. The Oratory is pale and less extravagantly decorated, although still solidly baroque in style. It has more of the appearance of an auditorium as St Philip Neri saw singing praise as a primary occupation of the Oratorians, hence the name.

Lost art

|

|

|

|

San Giovannino degli Scolopi |

||

History From 1351 to 1554 the site of an oratory called San Giovanni Evangelista. With the arrival of the then-new Jesuit order in 1577, and with the intervention of Duke Cosimo I who supplied the inheritance of a Giovanni di Lando of the neighboring Gori family, building began in 1579 to designs by sculptor Bartolommeo Ammannati, who designed the second north chapel for his own burial (in 1592). Ammannati is best known for the hulking fountain of Neptune in the Piazza della Signoria, upon the sight of which his friend Michelangelo is said to have cried 'Ammannati, what lovely marble have you ruined!' When he died responsibility passed to court favourite Giulio Parigi and then Alfonso Parigi il Giovane, who completed the work in 1661. The fourth south chapel was built 1692-1712 for Grand Duke Cosimo III. When the Jesuit Order was suppressed in 1775 the church passed to the Scolopian fathers, known more formally as the Order of the Scuole Pie. Restored in 1843 by Leopoldo Pasqui. Interior The ceiling fresco by Agostino Veracini dates to 1665, with stucco by Camillo Caetani. Other frescoes by Alessandro Fei (il Barbiere) and canvases by Jacopo Ligozzi. The painting Saint Francis Xavier Preaching to the Indians was commissioned from Francesco Curradi to commemorate the saint's canonisation (forth right chapel). The saint was a companion of Ignatius of Loyola and one of the first seven avowed Jesuits. He was sent to convert India, Japan and China, but his mission was characterised my racism and failure. He died on an island near China, having been refused admission, and his body was shipped back to Goa, where he'd started out, and where his toe relics attract pilgrims to this day. The painting here depicts some of the Indians wearing feather headdresses - a common misunderstanding. features a common misunderstanding as it shows some of the Indians wearing feathered headdresses despite the fact that Francis Xavier never went to America. The chapel housing this painting also has the remains of San Fiorenzo, placed here for the papal jubilee in 1700. The second left chapel, the one designed for his own burial by Bartolommeo Ammannati, has a Christ and the Canaanite of 1590 commissioned by him from Alessandro Allori which contains a portrait of Ammannati as St Bartholomew (standing with a crook) and his wife (kneeling with a book) the poet (and Jesuit supporter) Laura Battiferra. Her slightly hatchet-faced portrait in profile by her close friend Bronzino is in the Palazzo Vecchio. The couple were married here too. This altarpiece was one of three showing Christ's encounters with women that Allori painted, the others being with The Woman Taken in Adultery in Santo Spirito in 1577 and Jesus at the Well with the Samaritan Woman in Santa Maria Novella in 1575.

Lost art |

||

|

San Jacopo tra i

Fossi |

||

|

History The church already existed by the 11th century. The name refers to the ditch that ran by the second wall. The Vallombrosans moved here in 1170 and built a convent. In 1531 the complex was sold to the Augustinians. In the 17th century the church took its current form - a single nave with side altars, decorated with a wooden ceiling, in the centre of which is The Triumph of Faith with Saint Augustine in Ecstasy by Alessandro Gherardini from around 1690. The convent was suppressed in 1808 and became a barracks, losing almost all of its original decoration, excepting its carved and painted ceiling. In 1874 it passed to the Italian Free Church and in 1905 the Wesleyan Methodist Church, merged from 1946 with the Italian Evangelical Methodist Church. Interior Photos show a very bare, tall and narrow interior with a surprisingly ornate ceiling. Lost art  Fra Bartolomeo's Lamentation was painted for San Gallo, moved to San Jacopo tra Fossi, and is now in the Palatine Gallery in the Palazzo Pitti. It still glows but looks to have been chopped off at the top (see photo right) possibly by Grand Prince Ferdinando, who deprived many Florentine churches of their altarpieces, either by providing cash or replacement copies, and was known to be fond of adjusting the the sizes of said paintings to fit new frames. Vasari mentions in detail, and praises, a Raising of Lazarus by Agnolo Gaddi in this church. There is also a fresco fragment depicting The Raising of Lazarus by Gherardo Starnina, from c.1405, taken from this church in 1873 and now in the Santa Croce museum, where it's been since 1873. It is very like the work described, so it seems that Vasari made a(nother) mistake. Three works by Andrea del Sarto here are also mentioned by Vasari - a 1511 Noli me Tangere (now in the Andrea del Sarto Cenacolo Museum at San Salvi) and an Annunciation from 1512. These two pictures, and a Disputation painted later, were moved here when San Gallo was demolished in 1529. The Disputation and the Annunciation went to the Pitti Palace in 1627, where they can still be found. Antonio del Ceraiolo's Crucifixion with Saint Francis and Mary Magdelen is now also in the museum in the refectory at San Salvi. |

|

|

|

San Martino

del Vescovo |

||

|

History San Martino del Vescovo was the parish church of the Aligheri and Donati families. Founded in 986, it stood nearby in the via del Canto alla Quarconia. The current building, a former wool shop, also belonged to the Benedictine monks of the Badia. It was acquired in 1479 by the Compagnia dei Dodici Buonuomini founded by St Antoninus in 1444 to benefit the poveri vergognosi, that is 'the poor too ashamed to beg'. Merchants and nobles who had fallen on hard times, widows with children and the elderly - the handouts were made mostly to the heads of households, rather than the more usual destitute women and children. The confraternity had previously had the use of the old church. Requests for help were posted in the slot marked per le istanze in the church's façade. The confraternity still meet secretly every Friday afternoon to deliberate the distributing of funds, and all donations to help the needy rich are gratefully received. Interior Ten fine frescoed lunettes depicting the work of the Brotherhood and (flanking the altar) two scenes from the life of Saint Martin. They are possibly by Davide Ghirlandaio, but some sources see Dominico Ghirlandaio's hand, or at least his workshop, or even the young Filippino Lippi. The lunette left of the altar (see below right) shows Saint Martin Dividing his Cloak. This is by far the most commonly depicted scene from the saint's legend. Before becoming an ecclesiastic, let alone a bishop, he encountered a naked beggar outside Amiens and gave him half his cloak, only to later have a vision of Christ wearing it. The lunette on the right, The Dream of Saint Martin, has recently been attributed to Lorenzo di Credi. They were restored in 1971 and in 2011. A Byzantine Madonna and a Madonna and Child with the Infant Saint John by Niccolò Soggi, a pupil of Perugino. A reliquary bust of Saint Anthony attributed to Verrocchio is in a niche over the altar. Lost art Saint Martin Enthroned Between Two Angels by Lorenzo di Bicci (1380/90) is in the Accademia. It was commissioned by the Arte dei Vinattieri (Guild of Vintners) who met here and from that adopted Saint Martin as their patron saint Opening times 10.00-12.00 & 3.00-5.00 closed Saturdays and holidays

|

|

|

|

San Michele Visdomini |

||

|

History  There was an ancient church, known to have been enlarged by the Visdomini family in the 11th century, which was demolished in 1363 to make way for the east end of the Duomo and reconstructed here a few years later. The façade was added later (1577-1590) by Bartolomeo Ammannati. Interior The church has nice proportions for a small church. It's aisleless with greeny-grey walls with gilt detailing and three altars down each side. A painted ceiling fresco in the crossing from the 18th century depicts the Fall of Satan and is by Niccolò Lapi. Has a deep transept and chapels either side of the apse. 14th century fresco fragments and sinopie in the right-hand side chapel (see photo below) are attributed to Spinello Aretino. Altarpieces by Empoli, Poppi and Domenico Passagnano. The Passagnano is the unusual altarpiece subject of Saint John the Baptist Preaching. A plaque on the façade commemorates the burial here of Filippino Lippi. His tomb is lost, but the inscription is known to have begun with the words 'Disegno is dead now that Filippo is gone...' On the day of his burial all the workshops of the city closed as a mark of respect. Art highlight The uncharacteristically dark Pontormo over the central right hand altar, is the reason to visit. It's a Sacred Conversation which was commissioned by Francesco di Giovanni Pucci and was much in need of a clean. It's the largest painting in oil he did and one of the very few of his works still in its painted-for location. It was described by Vasari as the most notable panel ever made by this very rare painter. It's very unusual in being focused on Saint Joseph, the dedicatee of the altar, who hold the Christ child and to whom the Virgin gestures. It was removed for restoration at the end of November 2012 in preparation for an exhibition entitled Pontormo and Rosso: The Diverging Paths of Mannerism at the Palazzo Strozzi from 8th March to 20th July 2014. It's now back and looking even better (see photo below right) but without any notice telling you what it is, with the only clue to its status being that it's the only altarpiece that's properly lit. Details of a figure found during the restoration sketched on the back are here.

The sacristy

|

|

|

|

San Pancrazio |

||

|

Lost art |

|

|

|

San Pietro in

Celoro |

San

Salvatore al Vescovo |

|

History An ancient parish church dating back to Lombard times, with the first documented mention being from 962. Dedicated to an obscure blessed Peter in 996. Possession by the Ticino monastery is mentioned in 1081 and in 1032 the description "in celum aureo" is used, then popularised as "celoro". In 1448 as it was so near the Duomo that the church was suppressed by Nicholas V and became the archive and library of the Cathedral Canons, who also used it for meetings from 1680. The books and manuscripts had all been moved elsewhere by the late 18th century, it is said, but when I pushed open the door and snuck in in 2015 it looked like a library to me, which fact was confirmed by the helpful woman sitting working there.

|

History The church backed onto the Archbishop's Palace, hence the name (more strictly Arcivescovado). Documented from 1032 but probably dating back to the 9th century. The church seems to have been rebuilt in 1221, possibly by Arnolfo di Cambio. The bi-coloured Romanesque façade is one of only three original antique marble façades in Florence, the others being Santa Maria Novella and San Miniato. Partially reconstructed by Giovanni Antonio Dosio in 1584. The façade was rebuilt in 1895 when the piazza was enlarged Interior Major interior work by the architect Bernardo Ciurini in 1737, with fresco decoration including The Adoration of the Shepherds and The Transfiguration by Giovanni Domenico Ferretti in the choir and the dome of the choir respectively, and The Ascension of Christ by Vincenzo Meucci on the ceiling of the nave. Lost art The Apocalyptic Christ (Son of Man) - an altarpiece by Giovanni da Milano (pinnacles in the National Gallery London, two of the main panels in Milan and Turin) is thought to have been painted for this church for Petro Corsini, Bishop of Florence from 1362-1369. But there are several other theories. |

|

|

Santa Margherita de' Cerchi |

||

|

History Dedicated to Margaret of Antioch, first recorded in 1032. The major patrons, with chapels in the church, were the Cerchi, the Donati, and the Adimari families, with the latter two eventually leaving patronage to the Cerchi, hence the name. The church may quite possibly have been the location of Dante's marriage to Gemma Donati, but likely wasn't. It was certainly the Donati family's parish church and also contains several tombs of the Portinari, the family to which Dante's Beatrice belonged, as well as Monna Tessa, her nursemaid. Interior A messy and grubby little place. It's a dark church lit by a small window up high behind the altar and with weird and intrusive new age music playing. An iron balcony supported by iron poles above the door has the organ on it. There's one altar on each side, the one on the left has a carved relief over it, with a predella from another work underneath; the one on the right has a painting with a predella by Domenico di Michelino with Stories of Saint Margaret of Antioch. There highlight here is, though, the fine altarpiece of The Virgin Enthroned with Saints Lucy, Margaret, Agnes and Catherine of Alexandria by Neri di Bicci (see below) over the high altar.  In front of the this altar is the sepulchre of the Venerabile Compagnia dei Quochi, a company of cooks dedicated to the Spanish Saint Pasquale Baylon who is the patron saint of cooks as he is credited with the invention of zabaione. Visitors are encouraged to leave letters to Beatrice, who Dante didn't marry, asking her to fix their love lives. Which explains the box full of bits of paper by the left hand altar. There are a couple of paintings on the walls at the back showing Dante meeting women outside the church.

From the Codex Rustici, with the saint herself, who was eaten by the devil in the form of a dragon, but then regurgitated because she was carrying a cross. |

|

|

History  Founded in 1508, under the patronage of the Ricci family, in reparation for an outrage committed by one Antonio Rinaldeschi against an Annunciation painted on the side of the nearby church of Santa Maria degli Alberighi - he threw horse dung at it in 1501. The full story is below. 1610 saw a rebuilding, with the addition of the loggia, by the architect Gherardo Silvani (c. 1640). Interior The baroque interior, attractively proportioned, is an aisle-less and cube-y nave with two chapels either side, and was created in 1769-1772 by Zanobi del Rosso. The ceiling of the domed apse was frescoed with The Assumption of the Virgin by Lorenzo del Moro. Other scenes from The Life of the Virgin were painted by Giovanni Camillo Sagrestani on the side walls of the chapels. In the first chapel on the right there is a 14th century panel showing Saint Margaret of Antioch (for whom the church is sometimes named) inserted into a 17th-century canvas. The church is now also used for classical concerts, sometimes using the organ built in 1989.

An image cult

|

|

|

|

Santa Maria delle Grazie |

||

|

History  The Rubaconte bridge, named after Rubaconte da Mandello the podesta who decided to build it in 1237, was the third bridge to be built over the Arno, after the Ponte Vecchio and the Ponte alla Carraia. The first chapel was built on it more than a hundred years later, it had a miracle-working statue of the Virgin which led to the bridge being renamed Ponte alla Grazie, for the 'graces' attributed to the statue, and to more chapels, shrines and hermitages being built. The order of cloistered nuns called the Murate ("walled in") originated here. Of the chapels on the bridge the most substantial was the one on the Santa Croce bankside - Santa Maria delle Grazie (see photo below) built from 1371, and under the patronage of Jacopo Alberti and his family following its completion in 1394. Alberti founded the chapel having been denied the use of the family vault in Santa Croce for his son's burial following a dispute involving his allegation of the Franciscan's misuse of funds. Following the demolition of the bridge in 1873 a fresco of the Virgin and Child with Angels of 1313 was moved to this oratory (which was built in 1874 for the Alberti by architect Giuseppe Malvoti) where it remains over the high altar. Interior A sweet little space, dominated by pinky-buff marble columns and inlay. There are some small nuns' grills high up left and right and a pair of small flanking altars, the one on the right has a 19th-century painting of San Giuseppe by Giuseppe Ciseri. The altar on the left has a crucifix. The dome and vaults were frescoed by Olinto Bandinelli. In the lunette over the Tabernacle is The Crowning of the Virgin, in the lavendery cupola is The Trinity with Moses and David, and the corbels feature the Prophets Isiah, Jeremiah, Salomon and Aggeo. On the marble floor are the arms of the Alberti family. The church in art  Il convento del Ponte alle Grazie by Adolfo Belimbau (1930) shows the original chapel on the bridge, as do views of the bridge painted by Fabio Borbottoni in the late 19th century.

Opening times

Bibliography |

|

|

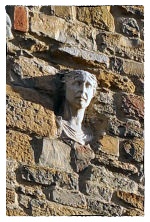

History  The legend that this church was founded by Pope Pelagius II in 580 is widely contested. A church has existed here since at least the 8th century, albeit in a different form, but the first recorded mention is in a document of 931. It passed to the Cistercians and was rebuilt in it current gothic form at the end of the 13th century, possibly retaining the walls and vaulting from the previous structure. Vasari says a 'meastro Buono' oversaw the building, but it's not known who he was. The church decayed as its fortunes declined during the 15th century and it passed to reformed Carmelites from Mantua in 1521 and the complex underwent rebuilding. The interior was renewed by Gherardo Silvani in the early 17th century, possibly to an earlier design by Bernardo Buontalenti. At his time the church acquired the ceiling frescos of The Life of St Zenobius by Poccetti and paintings by Cigoli, Pier Dandini, Passignano, Volterano, Vincenzo Meucci and Matteo Rosselli. Further altars, altarpieces, frescoes and stucco work were added in the 18th century and an inscription was found on a column in the chapel to the left of the apse marking it as the tomb of Brunetto Latini, a Florentine writer and Chancellor of the Republic, also known as Dante's master. The rough stone exterior had a marble façade designed for it by Alfonso Parigi which was never built. It was covered in plaster until a restoration in 1912-13, at which time some of the baroque additions were also removed. Interior A tall and very frescoed church - fragments mostly - but the nave and apse are oddly less decorated than the aisles. Dividing the nave from the aisles are rows of very chunky square columns. The rear right one and the pilaster facing it on the inner façade (see photo right) have frescos attributed to Mariotto di Nardo. Each aisle has three altars, the first one on the left has a Virgin and Child with Saint Francis by Matteo Rosselli. The pair of frescos either side of the apse, King Herod and The Massacre of the Innocents, are by Jacopo di Cione and detached and almost grisaille. In the chapel to the left of the sanctuary is an unusual painted wooden relief of the Virgin Enthroned (see photo below right) until quite recently thought to be Byzantine work of the 12th century, but following restoration is now considered to be by the Florentine Coppo do Marcovaldo. The restoration work also revealed that the plaster heads of the Virgin and Christ have cavities for relics, which were some of Christ's blood and a piece of the true cross. Carbon dating revealed that the wood is older than expected at that the cloth wrapping one of the relics is of Byzantine origin. Lost art The Carnesecchi Triptych by Masolino and Masaccio (c.1423/5), their first known collaboration, was, according to Vasari, in the Carnesecchi Chapel here - a triptych with the Virgin and Child Enthroned between Saints Catherine and Julian the Hospitaller. The side panel depicting Saint Julian (attributed to Masolino) is in the Museo Diocesano and the centre panel is said to be the one, formerly in Santa Maria di Novoli, a church just outside Florence, which was stolen on January 1st 1923 and has never been recovered. The Saint Catherine panel is also lost. A predella panel of Saint Julian Meeting his Wife After Killing his Parents (attributed to Masaccio) is in the Horne Museum. (But one of Saint Julian Tricked by the Devil Kills is Parents (attributed to Masolino) in the Ingres Museum, Montauban, is now not thought to be from this altarpiece.) The Carnesecchi Chapel also had, above the altarpiece, a fresco of The Annunciation, likely a lunette, and the four Evangelists in the vaults, by the young Uccello. Vasari also writes that the high altar had an altarpiece of the Coronation of the Virgin by Agnolo Gaddi, and that the apse had frescoes by Spinello Aretino depicting Stories of the Life of the Virgin and Saint Anthony Abbot. Only a fragment of the latter survives. A triptych depicting the Virgin and Child with Saints Mary Magdalene and Ansanus by Andrea di Cione (Orcagna), and now in the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, is thought to have been painted for the Baronci chapel, dedicated to Saint Ansanus, here. An inscription on the triptych records Tommaso Baronci as its commissioner, in 1350, and Ansanus, the patron saint of Siena, is an unusual dedicatee in Florence. Frescos in a similar style, showing scenes from the life of Saint Thomas, Tommaso's name saint, were discovered in the same chapel here in 1897. A marble scene of The Annunciation carved by Arnolfo di Cambio, formerly in the cloister here, is now in the Victoria and Albert Museum in London. Sandro Botticelli's Martyrdom of St. Sebastian (1474, now in Berlin) and his Lamentation (1499-1500, now in the best room in the Museo Poldi Pezzoli in Milan) where both here. The Lamentation is a half-size version of his high-altarpiece Lamentation painted for San Paolino up the road. It has his late-career flatness and mannerism-predicting elongated and bendy monumental figures, and was still over a side altar here in the mid-16th century. It might be the altarpiece which Vasari said was 'very beautiful, commissioned by Donato di Antonio Cioli, a manuscript illuminator at this church. It might be the altarpiece which Vasari said was 'very beautiful, commissioned by Donato di Antonio Cioli, a manuscript illuminator at this church.  Campanile The Romanesque campanile remains on the street corner, now much shorter and looking like the left third of the façade. High up and left of the two windows there's a half-bust of a woman (see photo right) known as Berta and almost certainly ancient Roman. Legend has it that she was a woman who made fun of a passing condemned prisoner who then cursed her and turned her to stone. Cloister The 16th-century cloister of the old convent remains behind the church. Opening times 7.00-12.00, 3.30-5.30

|

|

|

|

Santa Maria Sopra Porte

(Sovraporta) |

||

History First recorded in a document dated 23rd July 1038, the church was so named because it stood near the south gate of the old city walls (Porta Santa Maria). It was rebuilt in the middle of the 13th century and was used for the meetings of the Capitani di Parte Guelfa, who built their own palazzo next to it in the mid-14th century. The Prior, Federico de' Bardi had a chapel, dedicated to St Bartholomew, built onto the left side. In 1410 the church came under the patronage of the Parte Guelfa and in 1456 lost its role as a Collegiate Church and became an oratory dedicated to San Biagio. Damaged in a fire in 1706, which destroyed the art inside, rebuilt and then suppressed in 1785, in the 19th century it was deconsecrated and used as a fire-brigade barracks: the frescoes inside were mostly destroyed and the furnishings and possessions dispersed. These included the three pieces of stone supposedly from the Holy Sepulchre that had been brought back from the first Crusade and were used to start the fire for the Easter Sunday celebration of the Fuocco del Carro. Following deconsecration they were moved to Santi Apostoli (see following entry) along with at least two 15th-century antiphonals one of which remained at Santi Apostoli until the middle of the 20th century, with the other sold at Christie's in 2003 (see below). The building is now the Palagio di Parte Guelfa library. The double staircase entrance, once common in this area, before the demolition of the Mercato Vecchio and the Ghetto to make room for the Piazza Vittorio Emanuele II, today called the Piazza della Repubblica, is now the last such in Florence.

|

||

|

Santi Apostoli |

||

|

History  Legend, and a stone slab on the façade, has it that this church was founded in April 805 by Charlemagne, but its first documented mention is dated the 27th of April 1075. Most sources go with its being built in the 11th century, maybe even a century earlier so this is still probably the oldest church on this side of the Arno, with the exception of the Baptistery. The church was remodelled in the 15th and 16th centuries, the work largely funded by the Altoviti family. Another legend claims that Michelangelo convinced Bindo Altoviti, who planned more drastic rebuilding, to preserve the existing fabric. Bindo it was who offered Michelangelo refuge when he fled from Florence to Rome and whose famous portrait by Raphael, as a handsome youth, is in Washington. Since 2014 the church and parish have been entrusted to the Legionaries of Christ (Regnum Christi), an organisation which has been long plagued by sexual abuse scandals, especially those involving the order's founder Father Marcial Maciel, who was accused of sexually abusing many minors and fathering six children by three women. In December 2019, the Legion accepted responsibility for 175 cases of child sexual abuse by 33 priests, including 60 minors abused by Maciel, but a year later horror stories and accusations of cover-ups from the Pope on down continued to circulate. Controversy also surrounds the Legion's recruiting practices, elitist theology, and the it's multi-million dollar offshore holdings in tax havens. Façade The white and grey marble doorway from 152, in the unfinished 11th-century Romanesque façade, features the coat of arms of the Altoviti family - a rampant wolf - and is attributed to Benedetto da Rovezzano, who was also responsible for the font inside and one of the many Altoviti tombs. Interior The interior is said to have inspired Brunelleschi (who is said to have thought the building was truly ancient, rather than relatively-recent Romanesque) and used as a model for San Lorenzo and Santo Spirito. Rough brick at the apse end and above the seven Romanesque arches that divide the nave from the aisles. Very small clerestory windows make this a dark church. The decorated wooden ceiling was added in 1333. A row of sizable columns, made from green Prato marble, down each side separating the nave from the aisles. The ancient roman capitals at the top of the first pair of columns probably came from a baths nearby, the rest are copies. The right side has five shallow chapels, all baroquely decorated with four deeper and less decorated (and earlier?) chapels along the left side. They vary in decoration, but have mostly middling 16th century art. The first bay on the left has a very damaged fresco - only the heads of the Virgin and Child and two angels remain - and its more complete sinopia. To the left of the apse is a polychrome Eucharistic tabernacle of c.1512 by Andrea and Giovanni della Robbia. To the left of this is the wall tomb of Oddo Altoviti (who paid for most of the reconstruction work here) by Benedetto da Rovezzano, which seems to have originally housed the Eucharistic tabernacle. Opposite over a doorway is the tomb of Bindo Altoviti (1570) from the studio of Bartolomeo Ammannati. There is also the monument of Antonio Altoviti with busts of Charlemagne and Antonio Altoviti by Giovanni Caccini. The Romanesque semi-circular apse contains a not-well-lit altarpiece, a Gothic polyptych of 1382 of The Virgin Enthroned with Saints and Angels (see below) probably by Jacopo di Cione with help from his frequent collaborator Niccolò di Pietro Gerini. It came here from the convent of the Poor Clares in via dei Malcontenti (Montedomini maybe?) in 1950 to replace the Pentecost by Orcagna mentioned in Lost art below. The Virgin and Child are flanked by two angels and Saints Clare and Catherine of Alexandria. The four flanking panels contain Saints Lawrence, John the Baptist, Francis and Stephen. The predella has an Adoration of the Magi in the centre with more saints processing in panels either side. The white and green marble altar dates to 1901. Another altarpiece by Jacopo, La Madonna della Neve, was finally returned to this church in June 2024, it having been in storage following damage during the flood of 1966. It is in the fourth chapel on the right, and looks very the worse for its experiences.

The middle one the right side chapels (the Altoviti

chapel) has the

Allegory of the Immaculate

Conception, begun in October 1540 by Giorgio Vasari (the leftmost of the three in the photo

right) which is thought worthy of illumination.

It was commissioned by the already-much-mentioned Bindo Altoviti. Vasari also

painted a smaller version for the patron which is now in the Ashmolean Museum in

Oxford. He wrote of this work 'I wished to give Florence an example of my skill

since I hadn't previously made any painting of this type here, and, having many

rivals and much desire for fame, I resolved to excel myself.' The naked Adam and

Eve are bound to the tree of original sin with similarly constrained Old Testament prophets

and John the Baptist, as the pregnant Virgin

tramples a serpent - a complex illustration of a then-controversial doctrine,

previously illustrated by Mary's parents' Meeting at the Golden Gate and

not adopted as Catholic dogma until 1854. Lost art |

|

|

|

History Named for its proximity to the Ponte Vecchio, the church was first mentioned in recorded history in 1116 although the Romanesque appearance of the lower half of the façade suggests that it is much older. Exterior renovated in the 13th and 14th century. Of the original facade, only the marble work around the portal remains. The church passed to Augustinians in 1585. Between 1631 and 1655, the interior of the church was renovated to convert the original three aisles to an aisleless space. A crypt was added and the interior was redesigned to include a choir. Interior has a staircase by Buontalenti of 1574 taken from Santa Trìnita. The church was heavily damaged during WWII by German mines. The façade had to be taken down stone by stone for half its height and swiftly rebuilt. The church was also damaged by the 1966 flood and the Mafia bombing of the Uffizi in 1993. Deconsecrated since 1986, since 2015 the church has housed ' immersive digital art experiences' like Inside Dalí and The Da Vinci Experience (see photo below). Art highlights An altarpiece by Francesco Curradi of The Death of Saint Cecilia now here was painted for the demolished church of Santa Cecilia. Lost art Fra Angelico repainted part of an altarpiece here by Ambrogio di Baldese, in the Gherardini chapel, which is now lost. It was his earliest known independent work, confirmed by records of payments dated January and February 1418. It has recently been suggested that a predella panel in New Haven is part of this work. Choir books manuscripts from the 1330s, illuminated by the Master of the Dominican Effigies,  Pacino di Bonaguida and others, taken from this church,

are now in Pienza, But some miniatures stolen

between 1953 and the early 1970s remain lost. Montepulciano has many historiated

initials too. Pacino di Bonaguida and others, taken from this church,

are now in Pienza, But some miniatures stolen

between 1953 and the early 1970s remain lost. Montepulciano has many historiated

initials too.Opening times The church now houses ' immersive digital art experiences' like Inside Dalí and The Da Vinci Experience (see below). Diocesan Museum The attached Augustinian convent complex houses the Diocesan Museum which exhibits works of art taken from churches in the diocese of Florence, brought here for 'safety reasons'. These include a Virgin and Child by Giotto (see right) called The Madonna of San Giorgio alla Costa for the church for which it was painted. It was attributed to Giotto only in 1939 by German art critic Robert Oertel. For many years it was kept in Santo Stefano al Ponte where it was damaged in 1993 in the mafia bombing of the Uffizi. During its restoration a tear was left unrepaired in the left corner to mark the event. It is currently to be admired on the top floor in the Opera del Duomo Museum. Museum opening times 2025 update I have never found the museum open, despite what the website of the Piccoli Grandi Musei of Florence often told us. It now says 'Closed for renovation' and has for years. The site's What's On pages date to 2015.

|

|

|

|

|

||