|

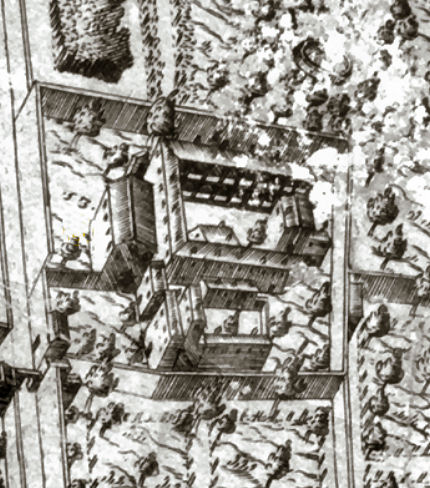

History The convent of La Crocetta, more formally known as the Monastero di Santa Croce, got its nickname from the small red cross the nun's wore on their robes, was founded by Suor Domenica da Paradiso, in 1511. Formally approved by Pope Leo X in May 1515, building work was finished by 1519, with the financial help of Cosimo de 'Medici. Expanded and renovated by Giulio Parigi in 1612, work which included the building of the corridors over the road which still remain (see right). From the late 16th century into the first half of the 17th the convent was a notable centre of musical performance. Suppressed in 1808 the complex has been put to various legal, medical educational uses in the years since, briefly returning to religious use in 1816, it was used in the years that Florence was the capital of Italy (1865-1871) as the Court of Auditors, the nuns having been moved, with the relics of their founder, to the via Aretina, to the east of Florence, where they remain. The former convent and church are now, following renovation work in 2008/9, used by the University of Florence's Faculty of Political Sciences and Law. The Hotel Morandi alla Crocetta incorporates the nun's chapel. Domenica da Paradiso Domenica Narducci, called Domenica da Paradiso, was a nun who acquired her name having been the daughter of a gardener who worked in the convent in Paradiso, a suburb of Florence. She took orders at the Augustinian convent of Santa Maria dei Candeli, where she was unimpressed by the spirit-sapping drudgery of the nun's life, especially for a nun with a peasant background. She fell ill and was allowed to leave the convent. There followed a short stay at the convent of Santa Brigida at Paradiso which was even more constricting and so she moved to Florence with some like-minded women, where the group so gathered around her fell under the Savonarolan influence of the friars of San Marco. But the protracted furore surrounding Dorotea da Lanciuole, another founder of a female religious house with a similar background to Domenica, who was found to have been faking her claim to have been miraculously surviving without earthly sustenance, led to her splitting from the Savonarolan Dominicans, claiming she had had a visitation from St Dominic himself. After having established her convent, with support from the Medici, who were happy to support an anti-Savonarola faction, she retained her influence, and reputation for controversy, through the Medici's expulsion and restoration and was later beatified. Miraculous images Before the founding of the nunnery Suor Domenica, on her way to SS Annunziata to pray before the celebrated miraculous Annunciation, heard a voice say 'Dominica, free me from this disgrace'. The voice turned out to be coming from a Nativity displayed in a nearby painter's shop, amongst images of lascivious subjects. This image was later placed above the altar in the nun's inner church. It was thought to be what saved the convent from a fire in July 1515, said to have been started by the devil. When the fire broke out Suor Domenica preyed before the the Nativity for help, and the Virgin told her to make the sign of the cross, which did the trick. Following the fire the image was moved to the high altar of the convent's public church, and a painting depicting the miracle was installed. |

Lost art

Had The Visitation of Saint Anne by

Ghirlandaio, a panel painting. (Cadogan p244.) Also two by Francesco Morandini

(il Poppi) - a Crucifixion and a Finding of the True Cross,

both now in the Andrea del Sarto Cenacolo Museum at San Salvi, where there is

also a Gloria di angeli e santi by Giovanni Baldacci. |

|

|

History Also known as the Oratorio dei Pretoni. Formerly the church of San Salvatore and belonging to the confraternity of that name, until in 1312 it became a hospice for elderly priests and pilgrim clerics and was dedicated to San Jacopo. Modernised for Archbishop Alessandro de' Medici 1585-88 by architect Giovanni Antonio Dosio. . Suppressed by Grand Duke Pietro Leopoldo in 1785. Since 2005 the oratory has been used as a classroom by the Accademia di Belle Arti. I found the church unusually open for an art exhibition in October 2025 (see right) Interior Aisleless with clerestory windows on one side. Two side-altars and a high altar. An organ gallery built into the doorway houses and organ still in use. After the completion of the late-16th-century renovation Giovanni Balducci painted these three altarpieces and a fresco cycle of Scenes from the Life of Christ (1590) around all the walls. All are in various states of damage. Here too is the tomb of Arlotto Mainardi, the parish priest of San Cresci a Marcoli between 1426 and 1468. Famous for his practical jokes, Mainardi is the subject of a famous 17th-century painting by Il Volterrano (Baldassare Franceschini) The Parson's Jest (see below), now in the Palatine Gallery of the Pitti Palace. The inscription on the tomb reads 'Piavano Arlotto had this sepulchre made for himself, and for anyone who wants to join him'. This is thought to be a later revision of the original inscription. It is under the glass panel near the entrance visible in the foreground of the photo below right.

|

|

|

History Originally the hospital of San Sebastiano, founded in 1464 for victims of the plague on land granted to the hospital of Santa Maria Nuova. Later used by two Franciscan orders of nuns (from Santa Maria a Montedomini and Santa Maria a Monticelli). Following the suppression of the two convents in 1810 they were merged and redesigned in a neo-classical style as a hospice for the elderly in the early 19th century by Giuseppe del Rosso, becoming a workhouse in 1860, then being known as the Pia Casa di Lavoro. The church of the Monticelli was deconsecrated during the 19th century rebuilding, being divided into two floors and becoming a dormitory. The other church, which had belonged to the Montedomini, which had been consecrated in 1573, was retained. It has a vault painted with The Virgin holding her Child out to San Francesco by Agostino Veracini in the 18th century, and a nun's gallery, not surprisingly. It became a parish church in 1816. It is also said to house a large wooden Crucifix and a copy of the Madonna of the Harpies by Andrea del Sarto. There's also The Death of San Romualdo by Giuseppe Grifoni, from Santa Maria degli Angeli. A wing of the hospice used as a military hospital from 1894-1938 has painted decoration by Galileo Chini. The complex is now partly also used by the University. Lost art An action-packed Martyrdom of Santo Stefano (1597) by Ludovico Caldi (Il Cigoli) commissioned by Zaccaria Tondelli for this church, is in the Palatine Gallery in the Pitti Palace. |

History Founded in 1332 by Basilian monks, known as Ermini (Armenians). At the end of the 15th century it was used as a hospice by the Congregation of the Priests of the Holy Ghost - a glazed della Robbia terracotta roundel with a (headless) white dove on the wall facing Via San Gallo is a relic of this time. Various alterations, including a reorientation, until taken over in 1939 by Methodists. Now the home of Seventh Day Adventists Church. The most recent renovation work was in 2008.  Lost art There are six panels from an altarpiece by Agnolo Gaddi in the Alte Pinakotek in Munich from c.1393/96. Two panels from the main register are full-length Saints Julian and Nicholas, with the four predella panels showing scenes from the two saints' lives, two each. They were thought to have come from the chapel devoted to Saint Nicholas at SS Annunziata, but a recent theory has the altarpiece being commissioned by banker and merchant Gabriello Panciatichi for this church. The argument involves 18th century descriptions of this church mentioning an altarpiece of similar iconography, and Panciatichi having paid for an altarpiece with the same saints prominent in a church near Pistoia. |

|

|

History A Dominican convent built around 1297 for the nuns that had come to Florence from San Jacopo in Ripoli in 1292. The façade was decorated with a fresco by Fra Angelico. Suppressed in 1808, the complex became a military hospital in 1838. In 1930 the church was made into a lecture hall. The whole complex saw major restoration work in 1982. Currently it houses the Military Centre for Forensic Medicine and a museum of Military Medicine. The cloisters The larger of the two cloisters, built between 1560 and 1580, is visible from the via Cherubini, the wall on the fourth side of the cloister having been pulled down in 1924 to make this possible. In the same year a Monument to the Fallen Doctor was created by sculptor Henry Minerbi and installed in the centre of the cloister. It commemorates the Italian doctors who were killed in World War 1, with bronze figures cast from  the metal of the Austrian guns,

melted together with the medals of medical officers.

the metal of the Austrian guns,

melted together with the medals of medical officers.Lost art Biagio D'Antonio's Virgin and Child with Saints of c.1470, now in Budapest. Vasari attributed the altarpiece, then still in this church, to Andrea del Verrocchio. Only with the publication of a monograph on Biagio d'Antonio by Roberta Bartoli in 1999 was the cat truly set amongst the pigeons, attribution-wise. Cosimo Rosselli's Saint Catherine of Siena as Spiritual Mother of the Second and Third Orders of Saint Dominic, from c.1499/1500 is now in the National Gallery of Scotland in Edinburgh. (It was in storage in 2021 when I visited but rebuilding and expansion was in progress). It is accepted as coming from here despite the lack of documentary proof. The gallery website says it may have been painted for the convent of Santa Caterina in Florence because three of Rosselli's nieces were nuns there, but Santa Caterina was never a Domenican house..

From the

Buonsignori Map of 1584. |

|

|

||

History The oratory of the Confraternity of San Gerolamo e San Francesco Poverino in San Filippo Benizi (as it is still named) was built at the south end of the Loggia of the Servites, opposite the Foundlings' Hospital, in 1599 for the Company of San Filippo Benizi, an order which which was later suppressed. In 1785 it passed to the Confraternity of Santa Maria della Pietà which had come from the hospital of San Matteo. In 1844 the Fellowship of San Francesco Poverino moved here too when their oratory in via San Zanobi was destroyed. Many works of art and fitting from these orders are said to be preserved inside. These works are said to include a miracle-working crucifix from the late 14th century and a terracotta figure from 1454 of The Penitent St Jerome. The building has recently undergone restoration work, but it's only open for services, at 10.00am on Sundays and Holy Days. This work included the restoration of the central ceiling fresco representing San Filippo Benizi in Glory painted by Gennaro Landi in the 18th century. Scenes from the life of San Filippo Benizi were also frescoed in the Chiostrino dei Voti of the church of Santissima Annunziata across the piazza by Andrea del Sarto and Cosimo Rosselli. The funeral service of English art historian John Pope-Hennessy was held here, following his death in October 1994. In recent years it seems to have been put to appropriate use as a centre feeding Florence's poor and homeless. |

|

|

|

History The Confraternity of St Joseph, founded in 1405, met in a small oratory near the Ospedale del Tempio. A miracle-working painting of The Virgin and Child on the corner of via San Giuseppe brought them sufficient offerings to pay for the present building. The church was designed, according to Vasari, by Baccio d'Agnolo. Building began in 1519, consecration followed in 1522 and the work was completed in 1583. In that year the complex passed from the Confraternity to the Friars Minim of San Francesco di Paola. In 1754 the interi  or was frescoed by Sigismondo Betti and Pietro

Anderlini and in 1759 a new façade was built. or was frescoed by Sigismondo Betti and Pietro

Anderlini and in 1759 a new façade was built. When the Friars Minim were suppressed by Grand Duke Pietro Leopoldo in 1784, the convent was put to other uses and the church was made a parish church. The doorway, possibly based on a design by Michelangelo, was added in 1852. The decorated oratory and campanile were added in 1934 to the original designs by Baccio d'Agnolo. Interior Aisleless and baroque with three deep chapels on each side and a full-width choir with a hanging crucifix over the high altar. The frescoes on the barrel-vaulted ceiling and over the choir are by Sigismondo Betti, with trompe l'oeil architectural perspectives by Pietro Anderlini. The flooring had to be remade after the flood of 1966, the pavement of the first chapel on the right (see below) giving an idea of the flooring destroyed by the flood. The choir and inner facade have nine canvases by Francesco Bianchi Buonavita dated 1650. The marble high altar was made in 1930. Two works by Santi di Tito. A damaged Virgin and Child by Taddeo Gaddi which, along with a carved wooden Crucifix, belonged to Santa Maria della Croce al Tempio, is mentioned but wasn't visible in the church on either of my two visits. And the rectangular painting that is in the central chapel on the right, where the Gaddi should be, looks to have been fitted in by chipping bits out of the existing stone frame. But one chapel does contain that rare thing - a 20th century fresco, done in 1933-4 and very flood damaged.The Crucifix is the one that used to be carried by the hooded 'Battuti Neri' from the nearby church of Santa Maria della Croce al Tempio as they accompanied condemned criminals along the Via dei Malcontenti to the scaffold outside the Porta della Giustizia. This road, on which San Giuseppe stands, is named for the condemned who walked down it who were first brought to a chapel which stood near the current church. The miracle-working panel of The Madonna del Giglio mentioned above (and recently restored) is in the same chapel, and has been attributed to either the Master of Marradi or, more lately, Raffaellino del Garbo.

|

|

|

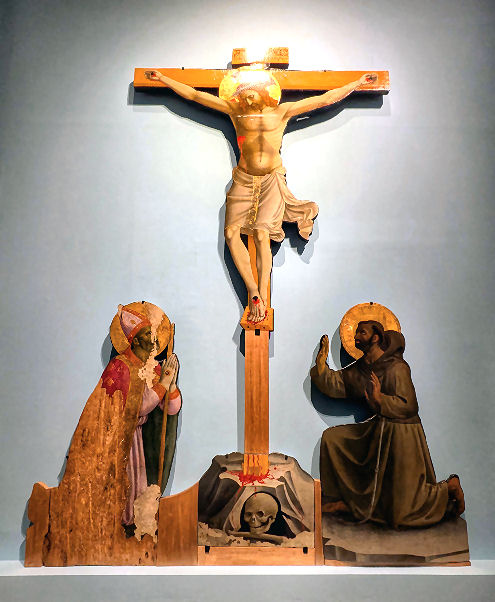

History An oratory belonging to the Compagnia di San Niccolò which was founded in 1417 as a scouts-like club for boys and youth to learn Christian doctrine and do good works. This church was built for them in 1561. Before moving here in 1564 they had been based in Santa Maria della Croce al Tempio. The name del Ceppo derives from putting offerings in a slot in the wall.  Interior In the atrium, on the left-hand wall, is a fresco by Pieter de Witte of the Virgin and Child between Saints Nicholas and Jerome from c.1585. In 1734 the ceiling was painted with The Virgin and the Trinity welcome Saint Nicholas into Paradise by Giovanni Domenico Ferretti, with trompe l'oeil architecture surround by Pietro Anderlini. Paintings flanking the altar by Giovanni Antonio Sogliani depicting the Visitation and St. Nicholas with Two Children of the Confraternity of 1521 were used as standards by the company carried at the head of processions. The Crucifixion of 1610 by Francis Curradi over the high altar replaced a panel of the Crucifixion with Saints Nicholas of Bari and Francis (see left) from around 1430 by Fra Angelico. Damaged in the 1966 flood, it is now in the sacristy here, following the completion of restoration in 1993. It got further work in 2017-18. It is formed of cut-around figures in silhouette, but the head of Saint Francis was cut off and sold, probably in the late 19th century, and is now in Philadelphia. A new head was painted and attached before 1909. The work was restored in 2016-18 and the positioning of the figures revised. Opening times There now seem to be occasional guided open days, for which at least €15 must be paid. |

||

History The oratory passed to the confraternity of San Pietro Maggiore, founded in 500, in the 16th century. In 1783 it became a parish church, taking the name of the demolished church San Pier Maggiore, but was deconsecrated in the next century. It is now home to the Dante Alighieri Society, which promotes Italian culture and runs language courses. Above the front door, which is the entrance to the cloister, is a glazed terracotta lunette of The Annunciation between two hooded brothers by Santi Buglioni, who was a young relative of the wife of Benedetto Buglioni, who headed up a rival studio to the della Robbia and probably trained with them. Santi took the Buglioni surname and inherited Benedetto's workshop. Interior Inside are a series of rooms and a cloister, decorated between 1585 and 1590 by Bernardino Poccetti, Giovanni Balducci, Bernardino Monaldi, Andrea Boscoli , Bartholomew Traballesi and Giovan Battista Naldini. The subjects include Martyrdoms of the Apostles (in the cloister), The Passion of Christ and The Life of the Virgin. Recent renovation has benefited the previously crumbling façade and brightened up its terracotta decoration. |

||

|

History Probably built before 1000, the church here was given to Benedictine monks from the Badia Fiorentina by the bishop of Florence in 1064, being originally dedicated to the saints Proculus (of Pozzuoli, a bishop of Verona in the 4th century) and Nicomedes. An inventory of 1441 tells us that San procolo had four side altars whose patrons were the Pannocchia, Villani, Arrighi and Valori families. Rebuilt in Romanesque style in 1622, when the orientation was reversed, this being the church with the high altar at the west end we have today. The building was then remodelled from 1739 to 1743, when it was acquired by the Confraternity of Sant'Antonio Abate dei Macellai, one of the four brotherhoods known as buche, which were known for flogging, strict discipline, and night-time prayer meetings. The other three such brotherhoods were at the churches of San Jacopo sopr'Arno, San Girolamo and San Paolo. The church was suppressed by the Grand Duke Leopold I and deconsecrated in 1778, when it was still controlled by the Badia, with its art mostly moved to the Badia. In 1786 it was sold to Cardinal Gregorio Salviati. From 1934 the church was used by Giorgio La Pira, a local politician who later served two terms as mayor, to celebrate masses for the poor - the Messa dei Poveri - at which food and money were given to the homeless and the sick (see black and white photo far below). These masses much later moved to the Badia and the church fell into disuse. The church was heavily damaged during the 1966 flood and closed, and then a portion of the roof fell in in June 2005, with accusations flying that the Salviati family had been refused permission to carry out restoration work which might have prevented the collapse. The roof was later rebuilt. In recent years there have been unsuccessful attempts to purchase the church by a nearby hotel and by the Bargello Museum to use as exhibition space. Prior to the eventual acquisition for the Bargello, in 2018 Michel Elefteriades, a controversial figure, bought the church from the Salviati family to make it into an art gallery, but the Italian Ministry of Cultural Heritage exercised its diritto de prelazione (right of refusal), not something it does often. Interior A Visitation attributed to Piero di Cosimo, Saint Proculus Healing the Hand of a Boy from 1739 by Gaetano Piattoli from over the main altar, a Virgin and Child with Saint Aloysius Gonzaga (the latter a 16th century Jesuit saint) also by Piattoli from 1739, along with an altarpiece by Matteo Rosselli Christ and the Wife of Zebedee of 1623 were removed for safekeeping in 2019 following the purchase of the church for the Bargello. Most of the other, more major works of art previously in the church having long since been removed. Some 14th century ceiling frescoes covered over by 18th century works are said to have been discovered when some of the roof collapsed in 2005. Lost art Three panels from 1305-10 from a dismembered pentaptych, almost certainly the high altarpiece here, by Pacino di Bonaguida, Saint Nicholas, Saint John the Evangelist and Saint Proculus, are now in the Galleria dell'Accademia. They are in the renovated rooms of the 13th and 14th century reopened in January 2022.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

History Built in the 11th century by the Vallombrosan Order (a branch of the Benedictines) as part of an abbey complex. The church was partly destroyed during the 1529 Siege of Florence, and reconstructed as it was, except for the portico, built in a 16th-century style. Vallombrosan nuns, called the Ladies of Faenza, who had seen their convent, San Giovanni Evangelista, destroyed in 1529, to build the Fortezza da Basso, due to the same siege mentioned above, came here after said siege. Interior A single aisle, Latin-cross design with a rectangular apse. The church is said to contain the early 15th-century frescos from a tabernacle once sited at the other end of the via San Salvi, said to be by Lorenzo di Bicci, or his son Bicci di Lorenzo, or both. Lost art The Vallombrosan nuns who came here in 1634 brought with them The Blessed Humility Polyptych (1341) argued to be by Pietro Lorenzetti, along with Humility's remains. The Blessed Humility of Faenza (born Rosanese Negusanti) changed her name when she founded the female Vallombrosan order, and the polyptych shows, around a central panel depicting Humility herself, thirteen scenes of her life, including Humility Dictating her Sermons and Humility Curing the Nasal Haemorrhage of a Nun. Most of the remaining panels are in the Uffizi, with two in the Berlin Gemäldegalerie. A triptych by Giovanni del Biondo of c.1370 depicting St John Gualberto Enthroned, with Four Scenes from His Life, commemorating the founder of the Vallombrosans, from the church here is now in the small room beyond the sacristy in Santa Croce.  Verrocchio's Baptism of Christ of c.1475, (see right) now in the Uffizi, was painted for this church (Verrocchio's brother,

Don Simone, was abbot here

sporadically between 1468 and 1478). It was painted when Leonardo was

apprentice to Verrocchio and Leonardo was almost certainly responsible for the left-hand angel

and the far landscape, they being so superior in execution and the angel

being painted using oil-based paint. Working in the latter medium was a

new thing in Florence at the time and would have appealed to Leonardo's

innovatory instincts, where Verrocchio himself was more enthusiastic about

the bronze sculptures at which he excelled. Vasari says that it was

comparing his own figures to the angel in this painting that caused Verrocchio

to throw down his

brushes and to devote himself totally to sculpture. But recent analysis

suggests that the stiff Christ is also the work of Leonardo. After the

siege (mentioned above) in 1530 the painting went to another Vallombrosan

monastery,

Santa Verdiana. It was rediscovered during the Napoleonic occupation,

brought to the Accademia in 1810 and transferred to the Uffizi in 1919.

Later in the 15th century Lorenzo di Credi, another of Verrocchio's

apprentices, painted a copy of the Baptism for the

Oratory of the Scalzi

which, following a fire there, was moved to the

church of

San Domenico in

Fiesole. Verrocchio's Baptism of Christ of c.1475, (see right) now in the Uffizi, was painted for this church (Verrocchio's brother,

Don Simone, was abbot here

sporadically between 1468 and 1478). It was painted when Leonardo was

apprentice to Verrocchio and Leonardo was almost certainly responsible for the left-hand angel

and the far landscape, they being so superior in execution and the angel

being painted using oil-based paint. Working in the latter medium was a

new thing in Florence at the time and would have appealed to Leonardo's

innovatory instincts, where Verrocchio himself was more enthusiastic about

the bronze sculptures at which he excelled. Vasari says that it was

comparing his own figures to the angel in this painting that caused Verrocchio

to throw down his

brushes and to devote himself totally to sculpture. But recent analysis

suggests that the stiff Christ is also the work of Leonardo. After the

siege (mentioned above) in 1530 the painting went to another Vallombrosan

monastery,

Santa Verdiana. It was rediscovered during the Napoleonic occupation,

brought to the Accademia in 1810 and transferred to the Uffizi in 1919.

Later in the 15th century Lorenzo di Credi, another of Verrocchio's

apprentices, painted a copy of the Baptism for the

Oratory of the Scalzi

which, following a fire there, was moved to the

church of

San Domenico in

Fiesole.A Coronation of the Virgin, a late (1511) work by Rafaellino del Garbo, was in the Louvre, but is now in the Petit Palais Museum in Avignon. Andrea Sacchi's The Three Magdalenes (c.1632/3) was here before going to the Uffizi. It was commissioned by Pope Urban VIII Barberini for a different church, probably. Also unclear is who the third Magdalene is, The second is Mary Magdalene de’ Pazzi, after whom the church of Santa Maria Maddalena dei Pazzi is named (and at which the aforementioned pope had two sisters cloistered as nuns). The third is a mysterious figure called St Mary Magdalene of Japan, India or China. Sutherland Harris in her definitive monogram on the artist observes that ‘she holds glowing coals, and was presumably roasted to death, but all the seven Mary Magdalenes martyred in Japan before 1633 were crucified or beheaded.’ There's is an oil sketch in the Palazzo Barberini in Rome and a chalk and wash drawing in the Royal Collection. The refectory - The Andrea del Sarto Cenacolo Museum The attached convent's refectory (see right) contains the fine and famous fresco of The Last Supper by Andrea del Sarto (see below right), painted for the Vallombrosans between 1525 and 1527. The relative severity of the treatment is said to be a reflection of the order's austerity. Judas is unusually not separated from the rest of the apostles by being placed on our side of the table or given clothing of a colour that stands out. It was said that Andrea painted himself as Judas after having betrayed and murdered his friend Domenico Veneziano. The story of the murder comes from Vasari, but as it turns out that Domenico lived for four years after the death of Andrea, so both stories fall to pieces. Vasari's stories, also involving Andrea's demanding wife, did lead, however, in the 19th century, to a play by Alfred de Musset and a dramatic monologue by Browning. Andrea was called del Sarto as his father was a tailor. Another story goes that the same defenders who were destroying everything that could be used by the besiegers in the 1529 Siege mentioned above, and who had partially destroyed the church, knocked down a wall to get into the convent but when faced with Andrea's Last Supper were so lost in admiration that they could not destroy it and, in fact, rebuilt the wall that they had already knocked down, the better to secure the painting. After the conquest of the city in 1530 the complex was given to Vallombrosan nuns, the monks having fled, and so the work was unseen until the the closing of the convent in the 19th century. Apart from the refectory (cenacolo) there's a long corridor and the former kitchen and washroom of the convent, used to display works of art since the acquisition of the complex by the state in the 19th century. The rooms are now full of altarpieces and fresco panels from other, usually demolished, churches, either by Andrea del Sarto or his contemporaries. There is some genuinely worth-seeing stuff here, often by artists you've scarcely heard of, and all hung so that you can get up close and appreciate. And then there's the Last Supper itself, which is one of the best, and said to have been Andrea's last major work. The faces, hands and feet are all equally, and extremely, expressive, the colours vivid and the paint looking fresh and unworn. I got given a leaflet about the cenacolo itself, but there are sadly no cards or books on sale dealing with the other works. Opening times I've never found the church open on several visits on weekday mornings The Cenacolo Museum Tuesday to Sunday 8.15 – 13.50 Closed Mondays, New Year’s Day, May 1st, and Christmas Day |

|

|

History In the via della Pergola, near an Arte della Lana house and by the grape pergola that gave the road its name, the Congregazione dei Contemplanti was founded by a Dominican friar from San Marco. In 1568 the baroque painter Santi di Tito became a member and designed this chapel for the Confraternity which was dedicated to Saint Thomas Aquinas, himself a Dominican. In the 17th century the oratory became a hospice for pilgrims but was suppressed in 1775. It was recently reconsecrated and services are now held here again.  Interior The vestibule has quadratura (trompe l'oeil) ceiling paintings from 1782 by Grix and Stagi. The nave ceiling has quadratura decoration from 1710 by Rinaldo Botti, with the Glory of Saint Thomas (see far right) painted by Camillo Sagrestani and Ranieri del Pace.

Lost art |

||

|

History Supposedly built on the site where Saint Ambrose himself stayed in 393, the church here was first documented in 988, but was probably older - the 5th century has been suggested, as has the presence of a Benedictine convent. It has been much rebuilt, notably in the late 15th century. The apse end, with its triumphal arch, as well as the baroque altar, was designed in 1716 by Giovanni Battista Foggini, with the gothic façade added in the 19th century, replacing the less-ornate gothic original. Interior Very much a used church, due to its proximity to the market and busy shopping streets, but also a church proud of its frescoes. It's wide and aisleless with an open timber roof. Four lovely chunky pietra serena Renaissance altars down each side. On the right as you enter is a detached fresco of the Deposition attributed to Niccolò di Pietro Gerini, large and in good condition, along with its sinopia (underdrawing), it was found behind the third altar on the left, as you can see from its retaining the outline of the arch of the altar embedded into it. The first chapel on the right, just after Cronaca's tomb slab in the floor, has a very faded fresco, the second has the lovely Madonna del Latte, flanked by Saints John the Baptist and Bartholomew. of around 1360 by the Master of the Rinuccini Chapel. It was formerly thought to be by Agnolo Gaddi. (Update May 2024 This fresco is due to be restored soon.) The third chapel has a dark an anonymous altarpiece, the fourth a bright Virgin and Child Enthroned.  By the steps is another, smaller

Virgin and Child attributed

to Giovanni di Bartolomeo Cristiani, and facing you, in the right-hand

side chapel behind the organ, is a lovely recently-restored triptych of the

Virgin and

Child with Saints Cosmas and Damian attributed to Lorenzo di Bicci,

with four more saints in the flanking panels (see right). By the steps is another, smaller

Virgin and Child attributed

to Giovanni di Bartolomeo Cristiani, and facing you, in the right-hand

side chapel behind the organ, is a lovely recently-restored triptych of the

Virgin and

Child with Saints Cosmas and Damian attributed to Lorenzo di Bicci,

with four more saints in the flanking panels (see right).In the apse are crowded frescos of 1832/3 by Luigi Ademollo depicting The Massacre of the Innocents, The Last Supper and A Scene from the Life of Saint Ambrose. They are where there were previously works by Filippo Lippi and Masaccio and Masolino. Coming back up the left hand side we begin with the highlight Cappela del Miracolo, to the left of the apse (see below right) with its fresco of The Legend of the Miraculous Chalice by Cosimo Rosselli, restored in 2016. It contains portraits of Rosselli's Florentine contemporaries, including a self-portrait in a black beret to the extreme left. The ceiling is also frescoed by Rosselli with the Four Doctors of the Church. Also in this chapel is a marble tabernacle by Mino da Fiesole made to house the miraculous and venerated phial of blood. The legend says that on 30th December 1230 a chalice which had not been cleaned was the next day found to contain blood  rather than wine by Uguccione, the parish

priest. This Eucharistic miracle made the church a

place of pilgrimage. The supposed miracles include plague prevention in

1340. rather than wine by Uguccione, the parish

priest. This Eucharistic miracle made the church a

place of pilgrimage. The supposed miracles include plague prevention in

1340.Mino's tomb slab is in front of the the chapel gate here too. Next is the Rosselli fresco's sinopia (see detail right showing a young woman with two children, who looks out at us in the finished fresco). The fourth chapel on the left has a dingy Saint Anthony Abbot with Tobias and the Angel by Raffaellino del Garbo, with an Annunciation above, the third has a Virgin and Child in Glory with Saints Augustine and Francis by Cosimo Rosselli. Next is a wooden sculpture of Saint Sebastian by Leonardo del Tasso, with a roundel of The Annunciation above, attributed to the workshop of Filippino Lippi, and the sculptor's tombstone in the floor in front. The second altar has a Visitation by Andrea Boscoli and the first a damaged fresco of The Martyrdom of Saint Sebastian by Agnolo Gaddi. Lastly on this side, as you return to the entrance, on the wall is a panel of the Virgin and Child with Angels and Saints by Alesso Baldovinetti. Another of the tombs of 15th and 16th century artists here is that of Andrea del Verrocchio who died in Venice in 1486 and his body returned here. Francesco Granacci, apprentice to Ghirlandaio and friend of Michelangelo, is also buried here. The paintings and fresco fragments here are mostly well-labelled, even if these are all a bit eccentrically translated. Lost art Filippo Lippi's Coronation of the Virgin (see below right) was commissioned for Sant'Ambrogio in 1441 by Francesco Marenghi, who is painted on the right under the Baptist's right hand, seemingly rising from a tomb, and paid for in 1447. It remained here until 1810, when it was stolen. It was later sold to the Accademia, from where it was transferred to the Uffizi in 1919. The frame is lost but a predella panel showing the Miraculous Infancy of Saint Ambrose (involving bees supping honey from his lips) is in Berlin (but not to be found in the Gemäldegalerie when I was there). On the left is supposed to be a self-portrait of Filippo Lippi in the garments of a Carmelite monk (looking out at us under the lily pot) next to St Benedict, probably. The centre foreground group includes three saints gazing out at us - the bishop Saint Martin and the martyr couple Eustace and Theopista, with their two children. This painting is described at length in lines 344-389 of Robert Browning's poem Fra Lippo Lippi, published in 1855 in his collection Men and Women. A Virgin and Child with Saint Anne by Masolino and Masaccio, painted probably around 1424 for the high altar here. Masolino painted Saint Anne and all the angels except for the top right hand one, painted by Masaccio who is also responsible for the Virgin and Child. It's been in the Uffizi since 1919. Fra Angelico's Virgin of Humility and Child, with Five Angels of c.1425 in the Thyssen-Bornemisza (on loan to Barcelona) was probably painted for an altar here. Sandro Botticelli's Virgin and Child with Saints Mary Magdalene, John the Baptist, Francis, Catherine, Cosmas and Damian from 1468/70 is his first known altarpiece. It was transferred (being then thought to be the work of Ghirlandaio) to the Accademia in 1808, and then to the Uffizi in 1946. The Madonna of Sant'Ambrogio by Andrea del Sarto, mentioned by Vasari, is long lost. Opening times Daily 8.00-12.00, 4.00-7.00 Città Rossa  On January 9th 1600 Donato Pennechini was crowned king of the Red City (Città Rossa) at a festive mass in this church and anointed with holy water by the prior. The Red City was one of a network of groups called potenze, organisations of artisans and labourers, mostly from the textile trade, set up to organise festivities and defend the honour of their neighbourhood, which would be a somewhat amorphous patch of the city, usually centred on an inn. Stone markers with the emblem of the Red City potenze are visible on the outside corner of the church. But on this occasion the church and state authorities took against what they saw as an outrageous 'mixing of the Sacraments with festivals and jests'. The prior of the church, Piero Manucci, who had taken part in the ceremony was sacked and exiled for a year, Costanza Giuntini, the abbess of the Benedictine convent which ran the church was deposed, and the Red Monarch himself was jailed and then exiled from the parish of Sant'Ambrogio. But the grand duke relented three months later to allow Pennechini, the 'old and poor wool beater', back into his parish. By the mid-1600s these traditional potenze had disappeared. |

|

|

History HistoryThe origins of the church and convent of Sant'Egidio (Saint Giles) are unknown, but are thought to have been Romanesque. The original complex, centred on the church of Sant'Egidio, had been run by the Frati Saccati, (Friars of the Sack) a mendicant order, suppressed by the Council of Lyons in 1274, whose Provençal saint the church was named for. Papal suppression didn't prevent the remaining friars living out their lives in the order, which remained here until at least 1286. The land and buildings thereby became available and were acquired to become the Hospital of Santa Maria Nuova, which was founded in 1288 by Folco Portinari, the father of Dante's Beatrice. The hospital expanded during the 14th century, but the first rebuilding of the church came following the old church's destruction in 1418, when it was enlarged, to designs by Bicci di Lorenzo, and new painted decoration added. This work was implemented by the then spedalingo (hospital prefect) Michele di Fruosino da Panzano, who also commissioned the fresco (see far below left) of Pope Martin reconsecrating the church in 1420, which shows the spedalingo kneeling before the pope and kissing his ring. The present appearance of the church is the result of a 16th century restructuring, attributed to a plan by Bernardo Buontalenti (1528-1608) and carried out by Giulio Parigi in 1611. The terracotta lunette of The Coronation of the Virgin over the entrance (see above) is a copy of the original by Dello Delli from c.1420/24 which is in the hospital museum. Interior Aisleless and boxy with a pair of tall pietra serena altars either side, the second on the left featuring a Deposition by Allori most dark and dingy and in need of cleaning. There's a double-tier nun's gallery at the back, which I'd not seen before, with some heavy-duty grill work, and there are more grills on the left-hand side. Much middling 17th century art. The 15th-century frescos that decorated the walls were covered by four classical altars in pietra serena (two on either side) during the 16th-century rebuilding by Buontalenti, who is also partly credited with the steps in front of the high altar. The baroque balustrade, which blends stylistically with the altar in patterns of semi-precious stones is later. Facing the steps are the tombstones of the Portinari family. The ceiling decoration is the result of the collaboration between Giuseppe Tonelli who took care of the painted architecture and Matteo Bonechi who added the figures in the first half of the 18th century. The earliest surviving Eucharistic tabernacle in Florence is said to be the 1450 marble panel set into the wall here by Bernardo Rosselino, with a gilt bronze door by Ghiberti. Lost art An almost square Annunciation panel by the Master of the Straus Madonna (c.1395-1405) from the hospital is in the Accademia. Fra Angelico's Coronation of the Virgin, now known as the Paradiso, painted around 1435 (see right) originally sited over an altar on the rood screen here and mentioned by Vasari in his description of Sant'Egidio, has been in the Uffizi since 1948. It's iconography comes a vision of Saint Bridget, as ecounted in her Revelationes. The cult of Saint Bridget flourished in Florence at the time, with a Bridgettine monastery built outside the walls called Paradiso. Two long predella panels, showing The Marriage of the Virgin and The Dormition are in San Marco. Also on the rood screen would have been a sweet altarpiece painted between 1434, when it was commissioned by Michele di Fruosino, rector of the hospital, and 1439, when it was delivered, by Zanobi Strozzi. It was placed on an altar dedicated to St Agnes and has been identified as the Virgin and Child Enthroned with Four Angels, now in the Museo di San Marco. It was probably a pendant to the Fra Angelico Paradiso. A great six-panel cycle of frescoes (1439-1470) of The Life of the Virgin, commissioned by the Portinari family and highly praised by Vasari, which decorated the choir of the church was begun between 1439 and 1445 by Domenico Veneziano, with Piero della Francesca and Bicci di Lorenzo as his assistants. They painted three scenes, with Andrea de Castagno adding three more opposite between 1451 and 1453. The final unfinished panel was completed, around 1461, by Alessio Baldovinetti. All of it is now lost, with only some unrevealing decorative panels remaining, as well as a sinopia (underdrawing) by Domenico Veneziano of a nude woman with perspective lines, these fragments being now installed in the refectory of Sant'Apollonia. It is said that the cycle's depiction of hospital patrons was also a celebration of Cosimo de'Medici's flight from Florence in 1433, as many of the Medici partisans who engineered his escape from prison were depicted. It is during their painting these frescoes that Andrea de Castagno (according to Vasari) murdered Domenico Veneziano. He writes that Blinded with envy of the praises he had heard of Domenico’s talent, Andrea determined to be rid of him. He considered various ways of killing him, and one of them he put into action as follows. One summer evening, as was his custom, Maestro Domenico took his lute and made his way out of Santa Maria Nuova, leaving Andrea there drawing in his room. Andrea had declined his invitation to join him on a walk, saying he had some urgent drawing work to do. So Domenico went off and pursued his usual rounds of pleasure in the city. But on his way back, unknown to him, Andrea was waiting round a street corner, and with some lead weights he smashed both Domenico’s lute and his stomach with one blow, and also struck him violently on the head with them. Then he ran off, leaving Domenico half dead on the ground, and returned to his room in Santa Maria Nuova, and leaving the door ajar he sat back down at the drawing he had left. Stirring stuff, but unfortunately it has been proven that Veneziano lived for four years after the death of Andrea. The Adoration of the Magi, a hugely influential altarpiece by Hugo van der Goes (see photo right) has been in the Uffizi Gallery since 1900. (Along with some other pictures that had for a while been in the house in via Bufalini where Ghiberti had his workshop.) It was commissioned by Tomasso Portinari, a Medici agent working in Bruges whose family had long been major patrons of this church and hospital, and was painted by 1478. It was commissioned to go over the high altar, the choir having been decorated with scenes from the life of Mary (see paragraph above) but without one depicting the Nativity. Portinari and his wife and children are depicted on the wings of the altarpiece. It is the largest Flemish altarpiece ever painted - wider even than the Ghent Altarpiece. It came by sea from Bruges to Pisa and then up the Arno to Florence, where 16 men were employed to carry it from the harbour, through Porta San Frediano, to Sant'Egidio. It arrived in Florence on 28th May 1483 and replaced an older work by Lorenzo Monaco, painted  around 1420/22 and now lost, but possibly depicting the same subject.

around 1420/22 and now lost, but possibly depicting the same subject.Botticelli's Virgin and Child with Saint John and Two Angels painted for the hospital, having been previously ascribed to Filippo Lippi. The terracotta lunette relief of The Coronation of the Virgin over the entrance (visible in the fresco right) has been replaced by a copy. The original is by Dello Delli from c.1420/24 (with painting and gilding, now mostly lost, by Bicci di Lorenzo) and is now in the hospital. The life-size terracotta Christ Showing his Wound over the doorway to the the hospital cemetery (the Chiostro delle Ossa, destroyed c.1657-70) to the left in the same fresco is 'almost certainly' the one, also by Dello Delli, now in the Victoria & Albert Museum in London (see right). Doubts were cast on the V&A Christ being this one by Dello when a hollow in his chest, containing sand and a thorn, was found during restoration, suggesting that it was used as a reliquary. But closer examination has revealed that the hollow was excavated after firing, so probably later. For the hospital Dello also made a tabernacle of The Virgin and Child with Angels and Prophets now in the Bargello and a relief of The Crucifixion now in the convent of Careggi. An Old Testament cycle of frescos painted by Allori in 1576 for the woman's chapel in the hospital is now in the Innocenti Museum. They look very influenced by the Sistine Chapel. Bibliography John Henderson - The Renaissance Hospital Contains much about the hospital of Santa Maria Nuova and hence Sant'Egidio, especially in Chapter 4, the chapter dealing with hospital churches. |

|

|

|

Santa Croce |

||

|

Santa Maria degli

Angeli |

||

History The church of a convent established in 1507, when six pious Florentine women acquired a house in Via Laura, near Borgo Pinti, bought for them by Dionisio di Clemente, a wool merchant, to devote themselves to the religious life and do good works. As their numbers grew in 1509 they took up the Dominican rule and the building was enlarged and transformed into a real convent. The name was possibly chosen to echo that of Santa Maria degli Angeli . In 1784 Grand Duke Peter Leopold's reforms saw the convent converted into a school and then suppressed in 1808. The church was damaged severely by the flood of 1966 and was closed for forty years, only reopening in November 2006, restoration work having began in 1996. The nuns remain and the convent has housed a dormitory for female university students since 1990. The nuns, of the order of Saint Martha, also now welcome women boarders. Interior Small, Baroque and aisleless. Well-preserved and large altarpieces survive within, including The Archangels Michael and Gabriel by Francesco Curradi and a Miracle of Saint Dominic by Matteo Rosselli. A mannerist Presentation of the Virgin with Saints by Domenico Puligo (see right), painted for this church in 1525, was reportedly recently to be found in Santa Maria Maddalena dei Pazzi but it has now been returned following restoration. It features polychrome fictive sculptures of the Annunciation in niches on the façade of the temple that Mary approaches - an unusual example of such a scene foreshadowing events. An anachronistic group of Dominican saints cluster at the bottom of the stairs too - Antonino Pierozzi, Thomas Aquinas, and Vincent Ferrer on the left and Helena, Catherine, and Lucy on the right. These latter facts have lead to conjecture that the painting may depict girls entering into a nunnery. Puligo was a pupil of Domenico Ghirlandaio, a collaborator with Ridolfo Ghirlandaio and a close friend of Andrea del Sarto, for whom he also worked as an assistant. Vasari said he was lazy. The frescoed nave vault is by Giovanni Maria Ciocchi. The refectory has one end frescoed with The Last Supper by Rosselli in 1631 - the sinopia is in the Innocenti Museum. There is a bronze Young Saint John the Baptist, part of a lost holy water font, and a Crucifix by Giambologna.  Lost art A fragment, depicting the Virgin and Child (see left), from a fresco of the Pieta said by some to be by Fra Angelico from c1424-28 is kept in Santa Maria degli Angeli, despite it being from this similarly-named convent. The state of the fragment suggest and outdoor location, maybe from a tabernacle here before the convent. Miraculous figure During the expansion of the convent in 1530 workmen were demolishing a nearby house when a terracotta Virgin and Child was found in a recess in a wall. It was ceremoniously installed in the nun's choir, but every morning afterwards was found by the nuns to have turned its back on them. This was interpreted as communicating the Virgin's wish to be placed in the public church, where the figure was then placed. It remains in a niche on the left side of church.

Opening times

By appointment only |

||

|

|

History The Brotherhood from which the church takes its name was founded in 1343 was initially based by the old Prato Gate where there was a gallows. There was also a hospital of the Knights Templar, from which the order derived its name. This first church was built in 1361 but was destroyed to clear the ground outside the walls during the Siege of Florence. The Brotherhood moved inside the walls and in 1424 established a group called The Blacks who accompanied prisoners from the Bargello or Stinche prisons to the gallows outside the gates. They were dressed in black and hooded, and flagellated themselves (and were hence dubbed Battuti). At their head they carried a crucifix now kept in the nearby church of San Giuseppe. The Brotherhood was suppressed in 1785 by the Grand Duke Peter Leopold of Tuscany at the same time as he abolished the death penalty. The church was deconsecrated. It reportedly contains paintings from the 16th to the 19th Centuries, including a cycle of frescos once attributed to Bicci di Lorenzo, later to the Master of Signa, an anonymous pupil of his.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Santa Maria Maddalena dei Pazzi |

||

|

Interior

Lost art |

|

|

|

|

||

History A monastery that was founded in 1628 by the Discalced (barefoot) Carmelites, dedicated to the Saint Teresa of Avila, one of the founders of the order. It was built to a design by John Coccapani, who also designed the baroque church. Suppressed in 1808 and 1865. Initially used to house the homeless, with the nuns still in charge, it became a prison in 1866. Enlarged in 1875, the complex was damaged by the flood of 1966. With the creation of the Sollicciano prison a competition was announced in the early 1980s for projects that would result in community use of the ex-prison buildings. Nothing came of this, and the building still houses low-security prisoners, with a small part also currently being used by the University of Florence's Faculty of Architecture. The baroque church has a central plan with a dome topped by a hexagonal lantern.  Anna

Maria Redi (Saint Teresa Margaret of the Sacred Heart) lived here from 1764 to 1770.

She was from the family

of Francesco Redi, the famous physician of Arezzo, and entered the

monastery young, soon after finishing her education at Sant'Appolonia.

She died,

and was buried, here at the

age of 23. Her body had become swollen and disfigured by the disease that

killed her but days later she

had appeared to be miraculously incorrupt and as if she was merely

sleeping. Anna

Maria Redi (Saint Teresa Margaret of the Sacred Heart) lived here from 1764 to 1770.

She was from the family

of Francesco Redi, the famous physician of Arezzo, and entered the

monastery young, soon after finishing her education at Sant'Appolonia.

She died,

and was buried, here at the

age of 23. Her body had become swollen and disfigured by the disease that

killed her but days later she

had appeared to be miraculously incorrupt and as if she was merely

sleeping. |

History A convent founded in 1395 by notary Niccolò Manetto for Vallombrosan nuns from his birthplace. Restoration of the existing buildings and the building of a church took five years. It was originally named for both San Giovanni Gualberto and Santa Verdiana, the latter a nun from Castelfiorentino who lived for 34 years, in the early 13th century, in the convent of Sant'Antonio Abate, walled up in a cell there together with the two snakes which got into her cell towards the end, but whose presence she never revealed. Saint Francis himself is said to have visited her for counsel in 1221. For Giovanni Gualberto's story see my entry for the church of Santa Trìnita. More building work in 1425, thanks to the nuns' dowries and income from land left by Manetto. The convent was further enlarged in 1462, with a cloister built, with Medici money - some say Cosimo the Elder but it's more likely to have been his son Giovanni. Further work was carried out during the 16th and 17th centuries, including the acquisition of works by Pier Dandini, Pietro Sorri, Fernando Melani and Vincenzo Meucci. still said to be in place. In 1589 a cult developed here around a miracle-working terracotta sculpture of the Virgin and Child. Following suppression in 1808, after which the nuns returned, and 1866 there were plans to turn the complex into an abattoir and then a women's prison, which it became and during WWII was used by the fascists to imprison female partisans. In 1983 the prison at Sollicciano was finished and the inmates then here were moved there. It was then sold to the university and is now used by the Faculty of Architecture. The cloister often gets used for art exhibitions. Lost art The Baptism of Christ by Andrea del Verrocchio and Leonardo da Vinci originally in the church of San Salvi, was transferred to the church here. In 1810 it was moved to the Accademia and then into the Uffizi in 1959. |

|

History The church was attached to the Franciscan convent of Santa Chiara, founded in 1363, which occupied the whole block to the via dei Conciatori. Consecrated in 1448, but rebuilt in 1542, following frequent flood damage, by architect Antonio Lupicini, the church contained 'great works of art', we are told.

The interior has a nun's gallery. After the

Napoleonic suppression in 1808 the church and convent passed to the

company of Librai e Stampatori (booksellers and printers), so becoming

known as the Chiesa dei Librai. The convent was later used as a

laboratory and the church was deconsecrated and used for storage,

falling into a deplorable state, it was reported. It is said that it currently still

houses a printing press. Rooms in the convent were used as a theatre at

the turn of the 19th/20th centuries, where Eleonora Duse is said to have

performed.

|

||

History There was a small oratory here by around 1191, built in vineyards owned by the monks of the Badia Fiorentina. A church replaced the oratory in 1209 and was enlarged in 1243. Consecration followed in 1247 when the building was designated a parish church. It was badly damaged when the Arno flooded in 1557. The archbishop of Florence, Alessandro Marzi Medici, elevated its status to that of a priory and named Giovanni Niccolai as its first prior in 1608, a post he held until his death in 1642. Niccolai fortunately came from a wealthy family and so initiated renovation work on the church. By 1619 a new high altar of Carrara marble was added and the choir stalls and presbytery were completely renovated under the patronage of Niccolai and Bartolomeo Galilei, a relative of Galileo, a Knight of Malta, and steward to Leopoldo de' Medici. This work, by the architect Gherardo Silvani, did not include the facade but did result in the destruction of tombs, chapels and 14th century frescoes. The final stage of Silvani's renovation (the gilt green ceiling) was completed in 1665. The floor of terracotta tiles and pietra serena is patterned to reflect the design of the ceiling and was restored after the 1966 flood. The church is currently used by the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church, whose iconostasis is visible in the photo (see right).

Interior |

||

|

History In 1294 the newish silk merchants' guild, the Arte di Por San Maria, named for the road where most of them had their shops, was given responsibility for the care and education of Florence's orphans and foundlings. The two existing homes were found inadequate by 1419 and in that year a bequest by Francesco Datini enabled the guild to acquire land in near the church of Santissima Annunziata and they set about demolishing the ramshackle buildings on the site. The commission to design the spedale, named for the Innocents massacred by Herod, went to Brunelleschi, a goldsmith who'd only the sacristy in San Lorenzo to his name thus far. He began with the loggia, which was to prove influentially and is still impressive. His Chiostro degli Uomini (men's cloister - see right) and the long Chiostro delle Donne (women's cloister) are also highlights. In 1427, following the completion of the loggia, Brunelleschi left, and the work continued under Francesco della Luna. The spedale opened in January 1445 and ten days later the first foundling - called Agata Smeralda - arrived. There were 90 children by the end of the first year and 600 by the 1460s. Many were the children of female slaves - most prosperous families had at least one such domestic slave, the labour shortages following the plague of 1348 only making the situation worse. Children were mostly left at night, initially in a basin beneath a window to the right of the entrance, where a woman waited listening at the window above. Around 1660 a wheel (which can still be seen, behind a grill) at the left end of the loggia, was installed, and was used until 1875.

The church

The Museo degli

Innocenti |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||