History

San Michele was the name saint of the church of the monastery which began construction

here in 1295 by the Camaldolese Order - a branch of the Benedictines founded in 1012 by the

hermit St. Romuald (c.951-1027) at Camaldoli, near Arezzo, hence their

name. Don Rorlando of that order had been sent to Florence in 1294 to

establish the order there, a move suggested and initially funded by the

aristocratic poet Frate Guittone of Arezzo, who didn't live to see his

vision come to fruition, but whose piety and generosity Dante writes of in

his Commedia. That an order devoted to the hermit lifestyle should

want to establish itself in such an urban environment is thought to be due

to the then prosperity and wealth of the city and its nobles and

merchants. Within the previous few years Santa Maria Novella had been

built and Santa Croce and the Duomo had seen rebuilding and expansion. As

the foundations were being dug the bishop of Florence led a procession of

worthies to the monastery site, bearing gifts monetary and liturgical.

Onlookers also spontaneously threw money, amounting to 250 lire, which

equalled the amount the order had paid for the land, previously owned by

the Alluodi family. The complex was originally built to house just six,

including Don Rorlando. It amounted to a small church, cells, a refectory

and a meeting room. The original six monks, including Don Rorlando, must

have found the going tough, as they returned to Camaldoli after a few

years, and were replaced by another six, led by one Don Romualdo, who seem

to have faired better. Numbers then swelled from six to sixty and then to ninety,

so rebuilding was swift and considerable.

The history of the monastery was recorded in the Registro Vecchio,

begun probably in the 1360s, and the identical Registro Nuovo, both

kept by the monks, and the reason there is so much information about the

place, and why this page is so detailed.

The original church was small, austere, choirless and aisleless and served

just the monastic community throughout the 14th century. An unusual

feature was, by 1297, the chiesetta, a space running along the east

of the church solely for the use of female patrons. It had an altar, an

altarpiece and a grill through which the women could have limited contact

with the monks. A little later a choir for the monks was added, protruding

and making an odd L-shape sticking out from the apse end beyond the end of

the chiesetta. The early 14th century saw the convent grow and

become an established Florentine institution, patronised by rich families,

like the Spini and a native Florentine prior appointed (Don Filippo degli

Nelli) in 1322. By 1330 all twenty-two members of the community were

Florentine and it is thought to be the need to teach young novices the

liturgy that was second nature to the earlier monks from Camaldoli that

lead to the borrowing of none books from the convent of San Pietro di

Poteoli in 1322 and the establishment of a scriptorium to copy said books

within a decade.

The plague of 1348, which swept Europe and

saw off three quarters of the city's population, also resulted in the deaths of

seventeen of Santa Maria degli Angeli twenty-two monks. But the widespread

belief that the pestilence had been God's punishment for man's wickedness

resulted in considerable donations of money and children by those

remaining and benefiting from the drastic lessening and shifting of

resources, both human and financial, following the plague. The new donors

included an ironmonger. So, new money and old money together resulted in

the convent's best time yet for donations and building work, notably the

new chapter house to house the complex's growing number of monks.

Altarpieces too, notably from the workshop of Nardo di Cione. Lesser, but

still major, outbreaks of the plague kept levels of penitence and

donation steady through most of the 14th century, with the Albizzi family

the major financiers. It was mostly their money which paid for the major

work improving the church in the years leading up to completion on

Christmas Day 1374.

The complex was sacked in 1378 during the

rising of the ciompi, who saw Santa Maria degli Angeli as

unacceptably patrician-funded. A fire started in the infirmary soon spread

and resulted in the death of two monks. Only divine intervention, in the

shape of a miraculous gale, prevented the complete destruction of the

convent. Many early altarpieces were lost too. It wasn't until the wealthy

families, the Albizzi faction again foremost, regained power in 1382

that funding began to flow to repair the considerable damage wrought

during the sacking. The moribund scriptorium was revitalised at this time

too, and many burial chapels paid for and embellished with altarpieces.

During the Great Schism of 1409-1414 one of

the claimants to papal authority, Pope John XXIII, spent time in exile in

religious houses around Florence, from 1413 until is death in 1419. Since

1410 Pope John had worn a prized relic, John the Baptist's right index

finger, on a chain around his neck. In 1413 he secretly left this relic in

the safe keeping of Santa Maria degli Angeli, It's presence here was known

only to the monks, Cosimo de' Medici and and Matteo da Viterbo, the pope's

confessor. It was kept here for eight years, only passing into the

Florence Baptistery two years after John's death.

The late 15th century saw something of a decline, following the glory days

leading up to the installation of Lorenzo Monaco's altarpiece.

Remodelled in 1676, the church has a ceiling vault

fresco by Alessandro Gherhardini of 1700. The Chiostro degli Angeli has fresco

lunettes by Bernardino Poccetti, as does the dome of the Ticci Chapel off

of it from 1599. He also probably painted the altarpiece in the chapel.

The former refectory, off the Chiostro dei Morti, contains a 1543 Last Supper by Ridolfo del

Ghirlandaio (Davide's nephew) which was restored in 2000.

Suppressed in 1808, with the manuscripts going to the Biblioteca Laurenziana. The buildings are now used mostly by the university,

the church for lectures. Much of the rest of the complex has been absorbed

into the Santa Maria Nuova hospital.

A fragment of a fresco of the Pieta by Fra Angelico from c1424-28

is kept here, despite it being from a similarly-named convent of Santa

Maria degli Angiolini on Via della Collona.

The rotunda

In 1434 Brunelleschi was commissioned by Matteo and Andrea Scolari (the

heirs of condottiere Filippo Scolari aka Pippo Spano) to

design another church for the monastery. His original design was

probably inspired by ancient Roman temples and was the first centralized

building of the Renaissance. It consisted of a a domed octagon with 8

radiating chapels linked by a narrow passageway that pierced the apses and

served as an ambulatory around the octagon, and with a sixteen-sided

exterior. The altar would have been in the centre. Construction progressed

quite rapidly but was halted due in 1437 when the Scolari funds were

confiscated to help pay for the war against Lucca. The building had

reached a height of about seven metres. Around this time it acquired its

nickname of Il Castellacio - the broken-down castle. In the 17th

century the shell was finally given a simple wooden roof, but it still

deteriorated rapidly. I have a guidebook, written in 1900 by Edmund

Gardner, which describes Brunelleschi's building as a 'rather picturesque bit of ruin'. The

building, which had been put to various uses, was repaired and acquired

its current (and controversial) appearance after rebuilding in 1937 by

Rodolfo Sabatini. It was given to the university and, you will read

elsewhere, thus became known as the Rotonda degli Scolari, but I'd hazard

a wild guess that it's so called because of the name of the brothers who

first built it. In 1434 Brunelleschi was commissioned by Matteo and Andrea Scolari (the

heirs of condottiere Filippo Scolari aka Pippo Spano) to

design another church for the monastery. His original design was

probably inspired by ancient Roman temples and was the first centralized

building of the Renaissance. It consisted of a a domed octagon with 8

radiating chapels linked by a narrow passageway that pierced the apses and

served as an ambulatory around the octagon, and with a sixteen-sided

exterior. The altar would have been in the centre. Construction progressed

quite rapidly but was halted due in 1437 when the Scolari funds were

confiscated to help pay for the war against Lucca. The building had

reached a height of about seven metres. Around this time it acquired its

nickname of Il Castellacio - the broken-down castle. In the 17th

century the shell was finally given a simple wooden roof, but it still

deteriorated rapidly. I have a guidebook, written in 1900 by Edmund

Gardner, which describes Brunelleschi's building as a 'rather picturesque bit of ruin'. The

building, which had been put to various uses, was repaired and acquired

its current (and controversial) appearance after rebuilding in 1937 by

Rodolfo Sabatini. It was given to the university and, you will read

elsewhere, thus became known as the Rotonda degli Scolari, but I'd hazard

a wild guess that it's so called because of the name of the brothers who

first built it.

|

|

The Chiostro dei Morti

Illumination and Lorenzo Monaco

A renowned scriptorium flourished here from the 13th

Century. Vasari, writing a hundred years after, wrote that a Don Giacobbo and

a Don Silvestro were the monk/artists to be credited. This 'fact' seems to

be based on legend, however, and relies on the confusing of three separate

monks called Silvestro and his having the wrong Jacopo and Silvestro

buried in the same tomb. These errors lead to the citing of Don Silvestro dei Gherarducci

as a major artistic talent, an assertion which took a knock when his one

signature (on one of the dozen excised miniatures acquired by William

Young Ottley from the monastery, along with the Crucifixion

altarpiece mentioned in Lost art below) was found to be a late

18th/early 19th century forgery. Disagreement still rages, though, with

the four cuttings in the Fitwilliam Museum still safely attributed to Don

Silvestro dei Gherarducci and associates in the catalogue of their 2016

exhibition Colour - the art and science of illuminated manuscripts. Don Giacobbo dei Francheschi does seem to

have been a major contributor to the artistic excellence of the

scriptorium, though, even though the major part of the illumination work

in his time is now thought to have been contracted out to lay artists.

It was

here that Lorenzo Monaco established himself as both a manuscript

illuminator and a painter, although it's probable that his production of

panels and frescoes date to the years after he left. From whom he received his training is undocumented

and hence the subject of much scholarly conjecture and argument - Agnolo

Gaddi and Jacopo di Cione are mentioned, the latter seeming more likely.

Lorenzo became a fully-fledged member in 1391 and then a deacon in 1395,

after which his name disappears from the monastic legers, suggesting that

this is when he moved out

of the

monastery, but he maintained links - he painted the majestic Coronation

of the Virgin of 1414 (see below), the monastery sold him a house

and studio (right opposite the church doors and for a pittance) in 1415, and when he died (c.1424) he was buried

in the chapterhouse here.

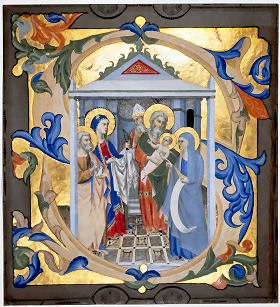

This is an initial S, with Christ Giving

the Keys to St Peter,

by Lorenzo Monaco. It is now in Washington, cut

from

a choir book now in the Biblioteca Laurenziana.

|

|

Lost art

The centre panel of Nardo di Cione's workshop's Coronation of the Virgin, 'almost certainly'

from the Albizzi chapel of the Ognissanti in the infirmary here, is now in the Victoria and Albert Museum in London.

The wings depicting saints are in the Alte Pinakothek in Munich. His

Trinity painted for the Ghiberti chapel in the rebuilt chapter house here is in the Accademia's Orcagna Room and his

Virgin and Child enthroned with flanking panels depicting Saints Gregory and Job

and predella panels showing The Trials of Job, is now in the small

room beyond the sacristy in Santa Croce. Both were installed in 1365.

Also dating to around 1365 is a very nice panel depicting The

Enthroned Christ Adored by Angels by Giovanni da Milano, part of a now

dispersed polyptych, now in the Brera, Milan.

Noli mi Tangere (probably) by Jacopo di

Cione, a a pinnacle panel from an altarpiece of c.1368/70 possibly from the Palagio chapel,

dedicated to Saint Peter, also in the rebuilt chapter house, is now in the National Gallery in

London. Two more panels said to be from the same altarpiece are in the MET in New

York (The Crucifixion), Denver (The Pieta) and Rome

and Luxembourg (Female Saints and Male Saints respectively.

Six pilaster saints are on loan to the National Gallery from the church of

Saint Mary Magdalene in Littleton, Middlesex, three more are in a private

collection. Six angels are in the Lehman collection too.

The Baptism of Christ, with Saints Peter and Paul and Scenes from the

Life of Saint John the Baptist by Niccolò di Pietro Gerini,

commissioned in 1386 by one of the monks, Don Filippo Nerone Stoldi, in

memory of his mother, for the Stoldi chapel in the infirmary is now in the

National Gallery

in London,

having spent some of the time between 1414 and 1580 at another Camaldolese

house, San Giovanni Decollato del Sasso.

(The flanking saints stand on a carpet imitating the design of one in the Nardo di Cione works mentioned above.)

A pair of panels depicting the Annunciation, now in the Feigen

Collection, are thought to have originally been pinnacle panels on this

altarpiece, with a Salvator Mundi, now in the Munich Alte

Pinakothek, over the centre panel. A Crucifixion by the same

artist, now in the Accademia, is known to have come from here, due to its

inclusion in the list of works looted by Napoleon, possibly having been

sited in the refectory.

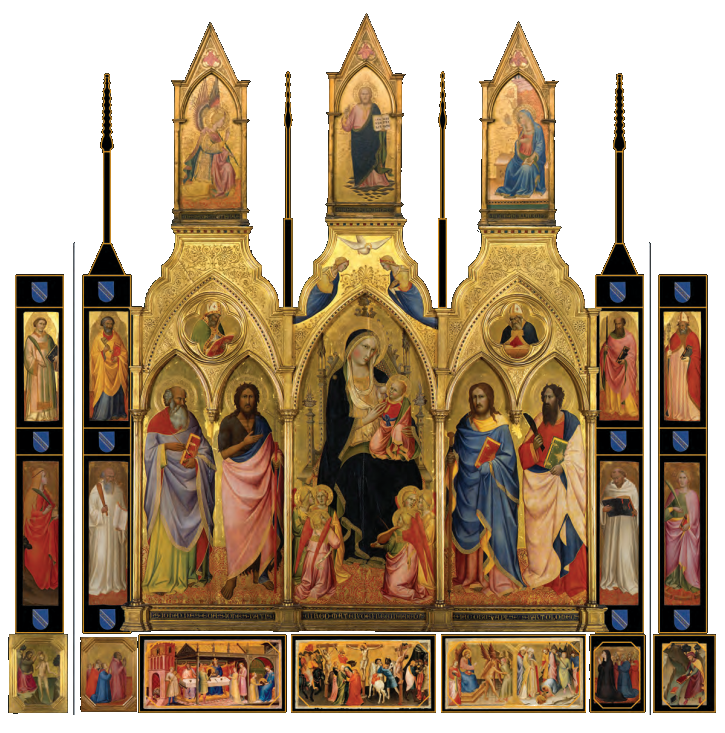

The Virgin and Child Enthroned with Saints John the Evangelist

and John the Baptist to the left and Saints James the Great and

Bartholomew to the right (see right), painted mostly by Agnolo Gaddi, assisted by

Lorenzo Monaco, in 1387-88 for

the Nobili Chapel (which survives) the chapel off the west cloister

founded by Bernardo di Cino Bartolini Benvenuti de’ Nobili, was

dismembered in 1808 during the Napoleonic suppression. The main tier is now in the Berlin

Gemäldegalerie (but was not on display when I was there in October 2015). Its predella panels

are early works by Lorenzo Monaco

which are in the Louvre (The Banquet of Herod, The Crucifixion, and a

single panel showing two Episodes from the life of the Apostle

James, all looking very much like finely-wrought manuscript

illuminations), the National Gallery in London (The Baptism of Christ) , the Alana Collection in

Newark, Delaware, and the Feigen Collection in New York. Four saints from the

pilasters are in the Clowes Collection, Indianapolis/Newfields Museum, and

four more, formerly in Göttingen, are now in the Berlin Gemäldegalerie.

These eight saints are usually given to Agnolo.

A Virgin and Child with Saints by Mariotto di Nardo, now in the

church of Santa Margherita a Tosina, outside Florence, is said to have

been painted for the da Filicaia chapel in the west cloister here in 1389.

An early work by Lorenzo Monaco, The Agony in the Garden, now in

the Accademia. It was painted around the time of his departure from Santa

Maria degli Angeli in 1395 to establish himself as an independent artist and

may have been a supportive commission by his former brethren.

A detached fresco fragment by Lorenzo Monaco showing

Christ in Piety (or The Man of Sorrows) from c.1411-1413 is

in the Innocenti Museum. It is said to have been in the Oratory of the

Alberti family here, now lost.

Lorenzo Monaco's only signed, and arguably most important, work is the spectacular

Coronation of the Virgin of 1414 (see right) painted for

the high altar here, now in the Uffizi. Saint Zenobius is here identified

by the Florentine lilies stamped into his halo, a detail surely hardly

visible to the naked eye. The three right-hand panels in the

predella are by Fra Angelico, who was assisting Lorenzo at the time. Another

Coronation of the Virgin by Lorenzo, called the San Benedetto

Altarpiece, of 1407-9, is in the National Gallery, London. It was

painted for the monastery of San Benedetto fuori della Porta Pinti, but

came here, when that monastery was demolished during the siege of

Florence, to

the Alberti Chapel. More panels from this altarpiece survive, three from

the predella are in the National Gallery and of the pinnacles, an

Annunciation is possibly one now in Pasadena and the Redeemer Blessing

in the centre could possibly be a panel once belonging to the art

historian Charles Loeser and still in private hands.

The odd trilobe-topped Last Judgement panel by Fra Angelico

from c.1425/28 was said by Vasari to have been sited to the right of the

high altar here. Whether this explains its original purpose, and where

it might have been sited before, continue to be controversial amongst

art historians. It could've been an overdoor, a chair back, or intended

for the cemetery here. It is now in the Museo di San Marco.

Andrea del Castagno's fresco of the Crucifixion of c.1453 (see

below right) now in the Cenacolo di Sant'Appolonia, includes the Virgin, Saints

John the Evangelist, Benedict and Romuald. It was in the fifth

cell of the second cloister here, above the garden. It was removed in the

20th century and is badly damaged. Another, even earlier, fresco of the

Crucifixion by Andrea from here is now in the offices of the hospital

of Santa Maria Nuova. It has the same saints, plus Mary Magdalene.

A fresco attributed to Davide Ghirlandaio of a

Crucifixion with Saints Benedict and Romuald, said to have come

from the cloister here, is in

the Andrea del Sarto Cenacolo Museum at

San Salvi.

Alessandro Allori's flower-filled

Coronation of the Virgin of 1593 is now in the left wing of the Tribune at

the Accademia.

The bronze Reliquary of Saints Protus, Hyacinth and Nemesius by Lorenzo

Ghiberti, from 1425-8, was set against the wall of the Ticci Chapel inside

the convent here, but with an arched opening above it onto the street,

enabling the veneration of the 3rd-century martyrs' relics by passers by.

These relics had been transported here on 7th January 1422, in a

procession, carried by Archbishop of Florence, Amerigo Corsini, from the

defunct San Salvatore

in Selvamonda, another Camaldolese abbey. This handsome reliquary,

sponsored by Cosimo and Lorenzo de' Medici. is now in the Bargello. Its marble step remains here, having been found in 2011.

Bibliography

George R Bent - Monastic art

in Lorenzo Monaco's Florence: painting and patronage in Santa Maria degli

Angeli, 1300-1415

from the Codex Rustici of c.1447

|

|

The Virgin and Child Enthroned by Agnolo Gaddi,

assisted by Lorenzo Monaco

(Reconstruction for an article in the January 2020 Burlington Magazine by

Dillian Gordon)

Lorenzo Monaco's

Coronation of the Virgin of 1414

|

In 1434 Brunelleschi was commissioned by Matteo and Andrea Scolari (the

heirs of condottiere Filippo Scolari aka Pippo Spano) to

design another church for the monastery. His original design was

probably inspired by ancient Roman temples and was the first centralized

building of the Renaissance. It consisted of a a domed octagon with 8

radiating chapels linked by a narrow passageway that pierced the apses and

served as an ambulatory around the octagon, and with a sixteen-sided

exterior. The altar would have been in the centre. Construction progressed

quite rapidly but was halted due in 1437 when the Scolari funds were

confiscated to help pay for the war against Lucca. The building had

reached a height of about seven metres. Around this time it acquired its

nickname of Il Castellacio - the broken-down castle. In the 17th

century the shell was finally given a simple wooden roof, but it still

deteriorated rapidly. I have a guidebook, written in 1900 by Edmund

Gardner, which describes Brunelleschi's building as a 'rather picturesque bit of ruin'. The

building, which had been put to various uses, was repaired and acquired

its current (and controversial) appearance after rebuilding in 1937 by

Rodolfo Sabatini. It was given to the university and, you will read

elsewhere, thus became known as the Rotonda degli Scolari, but I'd hazard

a wild guess that it's so called because of the name of the brothers who

first built it.

In 1434 Brunelleschi was commissioned by Matteo and Andrea Scolari (the

heirs of condottiere Filippo Scolari aka Pippo Spano) to

design another church for the monastery. His original design was

probably inspired by ancient Roman temples and was the first centralized

building of the Renaissance. It consisted of a a domed octagon with 8

radiating chapels linked by a narrow passageway that pierced the apses and

served as an ambulatory around the octagon, and with a sixteen-sided

exterior. The altar would have been in the centre. Construction progressed

quite rapidly but was halted due in 1437 when the Scolari funds were

confiscated to help pay for the war against Lucca. The building had

reached a height of about seven metres. Around this time it acquired its

nickname of Il Castellacio - the broken-down castle. In the 17th

century the shell was finally given a simple wooden roof, but it still

deteriorated rapidly. I have a guidebook, written in 1900 by Edmund

Gardner, which describes Brunelleschi's building as a 'rather picturesque bit of ruin'. The

building, which had been put to various uses, was repaired and acquired

its current (and controversial) appearance after rebuilding in 1937 by

Rodolfo Sabatini. It was given to the university and, you will read

elsewhere, thus became known as the Rotonda degli Scolari, but I'd hazard

a wild guess that it's so called because of the name of the brothers who

first built it.