History

The site of two earlier churches from the 4th and 11th centuries.

The first church, built outside the old Roman city walls, was supposedly consecrated by

Saint Ambrose of Milan in 393, and is reputed to be the earliest

church in Florence. Tradition has it that a Jewish widow by the name of Giuliana (who became Saint Giuliana) offered to finance this original church

were she to bear a son, who she would then call Lorenzo, after the Roman martyr

after whom the church was also to be named. Saint Zenobius is said to have been

present at this consecration and to have been buried in the church when he died

in 429. Serving for several centuries as Florence's cathedral the church was

rebuilt from 1045 in Romanesque style (see drawing from Codex Rustici of 1425,

left) being reconsecrated on 20th January 1060 by Pope Nicholas II, who had

been Bishop of Florence. This church was destroyed by fire in the early 15th

century.

The current church was built by Filippo Brunelleschi

between 1419 and 1469, with financial help from eight parishioners, including

Giovanni di Bicci de' Medici, who initially commissioned Brunelleschi to build

the sacristy chapel (now called the Old Sacristy) but to whom the entire church

was then entrusted in 1421. Brunelleschi's commitment to his work on the Duomo,

along with a period of financial and political unrest, halted work in 1425,

until in 1442 Cosimo de' Medici lent the Commune 40,000 florins, the interest on

which was to pay for the construction of the nave. In return the Medici were

allowed to put their arms here and in the crossing, the church thus became so

Medici-financed as to become virtually Medici-owned, their mausoleum, with some

minor chapels in the nave and transept granted by them to other families.

The degree of Brunelleschi's involvement is much argued over, with Cosimo de'

Medici's favoured architect Michelozzo often suggested as responsible for the

work after 1442. When Brunelleschi died in 1446 responsibility passed to his pupil, and

later biographer, Antonio di Ciaccheri Manetto, whose work has been much criticised,

most notably by Vasari.

Between 1515 and 1517 Giuliano da Sangallo, Jacopo Sansovino,

Baccio d'Agnolo and Michelangelo all submitted designs for the façade. The idea

was to recreate in marble the more ephemeral grandeur of the decorations erected

for the Medici Pope Leo X's triumphant entry into Florence in November 1515.

Michelangelo's was commissioned, but never constructed, although his later designs for

the reliquary balcony on the inner façade, the Laurentian Library and the new sacristy (now known as the Medici Chapel)

were. He wasted three years on the façade project - he made almost thirty trips

to the marble quarries and elsewhere and much marble was bought for a

project of a hugeness not seen since the building of the Duomo cupola - before

Pope Leo's death cancelled the project. It was Michelangelo's first

architectural project, and a major disappointment which dominates one of the

longest of his letters. The unused marble was then used for the Medici Chapel,

commissioned a little later by another Medici pope, Clement VII.

The church was restored, with the campanile added,

by Ferdinando Ruggieri in 1740.

Interior

The characteristic Brunelleschi calm inside is even more

striking after the bustle of the piazza outside - one truly needs the pietra

to be as serena as it can. Basilical in form and Romanesque in style but

gothic in its loftiness - the arches rest not on the capitals but on blocks

placed on each capital, called pulvins. Circular windows above the side chapels

and tall windows at clerestory level fill the interior with light. The white

coffered ceiling is not over-gilt, but the painted dome (the Apotheosis of

the Saints of Florence) by Vincenzo Meucci, dating to 1742, just after the

Ruggieri restoration, does rather spoil the austere effect with it's fluffy

rococo exuberance. It is also the final piece of Medici patronage, commissioned

by Anna Maria Luisa de' Medici, who died in 1743, and the Grand Duchy of Tuscany

then passed to Francis III of Lorraine. So this is not the least spoiled of

Brunelleschi's interiors, but Michelangelo's inner façade blends pretty well,

especially his reliquary balcony of 1530, and other later embellishments, in the

15th and 19th centuries, don't do too much damage to Brunelleschi's original

concept.

Another highlight is the cool cube of Brunelleschi's

sacristy, now called the Old Sacristy, said to be the first centralised

structure of the Renaissance and something of a dry run for Brunelleschi's Pazzi

Chapel in

Santa Croce.

It's an early work of his and so was actually finished while he was alive, with

it's tomb of Giovanni di Bicci de' Medici, who founded the family bank and who

financed the work here, and later decorative panels by Donatello. It has a

pleasing umbrella dome (see photo right) and Donatello roundels in the

pendentives depicting the Four Evangelists with desks for their attribute

creatures to sit on. His rather relentless frieze of cherubs is less pleasing.

Giovanni di Bicci de' Medici and his wife Piccarda Bueri, the parents of Cosimo

il Vecchio, have their sarcophagus under the marble vesting table in the centre.

Verrocchio's marble monument to Piero and Giovanni de' Medici, Cosimo's sons, set into

the wall here, dates from 1472. The door to the left of the altar in here is

rarely open and leads to a lavabo (see photo

right).

Donatello's Passion pulpit in the nave was recently restored

and had a scaffolding viewing platform allowing you to walk around three of the

crowded panels and admire them up close. The other one (the Pulpit of the

Resurrection) was then restored and both have now been finished. They were

his last works.

In front of the choir is the tomb slab of Cosimo il Vecchio, buried in the

crypt below. It was Verrocchio's first documented commission, from 1465.

Art highlights

There are six shallow chapels in each aisle, and the

altarpieces are mostly late 16th century and unimpressive. A document from 1434,

relating to the creation of chapels, issued by the prior and chapter here

instructs that, chapels be decorated with 'a square panel without a

canopy' known at the time as a quadro. This lead, it is said, to the

unified-space scenes, mostly sacra conversazioni, that we find here. The

decree was not entirely successful, however, as some families brought their

gold-ground polyptychs from the old church (see Lost

art

below). It worked better in the 1480s and 1490s in Brunelleschi's

Santo Spirito, where

the results still speak for themselves.

There's a 1523 painting by Rosso Fiorentino of the

Marriage of the Virgin in the second chapel on the right (the Ginori chapel)

in which Joseph is a uniquely curly-haired, beardless and youthful, not the

safely infertile widower that he's usually portrayed as.  Anachronistic

figures not part of the narrative (a friar, for example) have excited comment

even as early as Raffaello Borghini's book Il riposo in 1584, which takes

the form of a dialogue between Michelozzo and Vechietto. Anachronistic

figures not part of the narrative (a friar, for example) have excited comment

even as early as Raffaello Borghini's book Il riposo in 1584, which takes

the form of a dialogue between Michelozzo and Vechietto.

The fourth chapel on the right has an Assumption by Michele

di Ridolfo del Ghirlandaio (aka Michele Tosini) which is really not very good.

This is not a church that's big on frescoes, but Bronzino's squirmy

Martyrdom of Saint Lawrence from the late 1560s is, well, very

big. Very few of the mass of figures are clothed, but amongst the few that are

you'll find a self-portrait of Bronzino, with his teacher Pontormo and colleague

Allori. This was almost his last work, there was to be a matching one opposite

but Bronzino died before he could start it.

Behind the Saint Lawrence in the chapel in

the left transept (the Martelli chapel) is Filippo Lippo's Annunciation

from c.1440, commissioned by the heirs of Niccolò Martelli, who had died

in 1422. It is one of his best early works and something of a breath

of fresh air (see far right). It's an early example of the unified field

altarpiece. It's darker tones and (especially) the bravura representation of the

water-filled glass flask in the cunningly-created niche in the foreground

show the influence of Netherlandish art and techniques. The clarity of the glass

in the trompe l'oeil flask, through which light can pass unhindered, symbolises the Virgin's purity.

The predella has three scenes from the life of the dedicatee's name-saint

Nicholas of Bari. Donatello's gilded but tasteful tomb, erected in

1896, is in here too.

The chapel next to the sacristy contains a likeable Saint

Anthony Abbot Enthroned Between Saints Lawrence and Julian by the studio of

Domenico Ghirlandaio. Or it could be by an anonymous master called the 'Maestro

del Tondo Borghese', which seems to be the current thinking. It was returned

after a year's restoration in February 2019 - there had been 'a very aggressive

infestation of insects'. There's a fine tomb in here too, to Berta Moltke Ferrari

Corbelli, by Sienese sculptor Giovanni Duprè (1857–64) (see sexy detail above). I confess to

finding the same famed monument sculptor's figure of Astronomy, on the tomb of

astronomer Ottaviano Mossotti in the Pisa Camposanto

(click here) similarly alluring.

Campanile

By Ferdinando Ruggieri in 1740-41, commissioned by the last of

the Medici, Electress Palatine Anna Maria Lodovica.

Lost art

A triptych depicting The Virgin and Child

with Saints Anthony Abbot, Concordia, Andrew and Pope Mark (see right)

was painted by Jacopo di Cione in 1391 for the Rondinelli chapel, to

the left of the main chapel. It was transferred to the new family altar in

the new church after rebuilding, but is now in Honolulu.

Frescoes by Bronzino and Pontormo painted in the choir just before

the latter's death were criticised by Vasari and later destroyed during

18th-century renovations. The left wall depicted the Deluge, the

right wall the Resurrection, with the Martyrdom of Saint

Lawrence on the back wall. It seems that the painted Saint Lawrence

would have appeared to have been resting on the altar, within which a

relic of the saint was kept.

The church in art

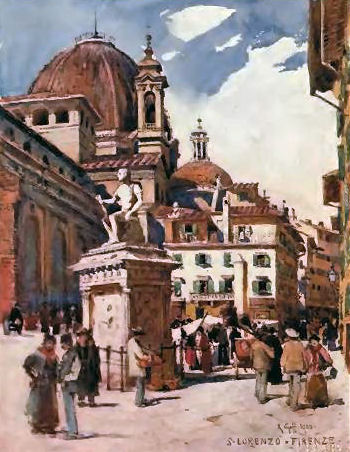

One of painter and etcher Robert Charles Goff's many scenes of

Florence and Tuscany is a rather impressive and unusual view of San

Lorenzo (see right). He was a follower of Whistler, an Irish Army

colonel who travelled much and retired to Brighton, where the Brighton

Museum staged a major exhibition of his work in 2011/12.

The cloister and crypt

Entry to the left of the church, beyond the ticket office. The

canon's cloister was designed by Manetti (1457-62) (see right) and

gives access to the crypt and treasury. Donatello is buried in the crypt,

as is his friend Cosimo il Vecchio, under their respective monuments in

the church above. The treasury is a room full of reliquaries in glass

cases.

The church in fiction

The counter-factual premise of Perspectives, the 2025

novel by Laurent Binet, is that Bronzino was murdered while painting his

last fresco here (detailed above) and that Vasari was employed to

investigate.

The church on film and TV

A spectacular road chase in the 1954 film Cronache di Poveri

Amanti based on a novel by Vasco Pratolini (translated into English as

A

Tale of Poor Lovers) ends with fatality and a flaming motorcycle

in front of the façade of San Lorenzo.

An episode in the second season of the American TV

series Da Vinci's Demons had a scene where Leonardo and Verrochio

are sitting on the roof of San Lorenzo (see below). Behind them is

the dome and campanile actually built centuries later.

Opening times

Daily 10.00 - 5.00

Sunday 1.30 to 5.30 March to October (closed Sundays rest of the year)

Medici chapels

Daily 8.15-1.50

closed 1st, 3rd and 5th Mondays and 2nd and 4th Sundays in each month

|

|

How San Lorenzo would have looked with

Michelangelo's

façade, created by studioDIM,

More here.

|