|

The word duomo comes from the Latin domus,

meaning the house of the Lord. So nothing at all to do with domes.

History

The earliest cathedral in Siena seems to

have been built on the hill called Castelvecchio and dedicated to Saint

Boniface, the 5th-century pope. This site became the convent of Santa

Margherita, and later the Istituto Pendola.

As the highest point in the city this has always been an important spot,

likely since a Roman temple to Minerva stood here. There's been a

cathedral dedicated to the Virgin Mary here at least since the 9th century, and a bishop's palace.

In December 1058 a synod was held here resulting in the election of pope

Nicholas II and the deposition of the antipope Benedict X.

The first documented evidence of plans to build a cathedral here date to

1136. The Siena-born Pope Alexander III is said to have consecrated the

site in 1179, but this seems unlikely. Work here began around 1220, but it wasn't until 1258 that the

overseeing of the work was entrusted to Cistercian monks from San Galgano, an abbey south-west of Siena, a famously

capable bunch, who provided the Operaio (works manager) until 1314. The enlarged Duomo was

dedicated in 1267.

By 1265 the basic work had

been complete and one of the monks, Fra Melano, went to Pisa to commission a pulpit from Nicola Pisano and

then in

1280 Nicola's son Giovanni was employed to work on the façade. By 1297

Giovanni had stormed off in a huff at the commune's accusations of

mismanagement of funds and materials. Then in 1317 it was decided that the

Duomo was going to be too small and in 1335 the foundation stone of a new and massive

structure was laid. The work was directed by goldsmith Lando di Pietro.

The plan was that the existing church should become merely the transept of

a much bigger building. This work was begun but cracks and errors halted

the work, which resumed but was finally halted by the plague of 1348, as

the population halved and funding dried up. In 1350 the foundations were

found to be woefully inadequate and the materials used so far to have been

substandard. The Florentine architect Benci di Cione was brought in

to advise and he advised that if the building continued it would fall

down. The remains of this extension, largely the right aisle,

still speak of Sienese ambition and hubris and

are now used as a car park and the Museo dell' Opera. The space was filled with the Bishop's Place, removed in the 19th

century, with the four large windows added in 1898. The proposed new

façade, now called the Facciatone, also remains, and you can walk

along the top.

During the 1920s the art historian, and mistress and

biographer of Mussolini, Margherita Sarfatti proposed that this pre-plague

project finally be completed.

The exterior

The gothic façade, first entrusted to

Giovanni Pisano at the end of the 13th century. He was probably

responsible for the design of the lower level. This facade, covering the

previous plain masonry, was sort-of finished in 1377, but

it was not until 1878 that the poor-quality mosaics, made in Venice, were added in the

topmost triangular pediments, under architect Giuseppe Partini, with the

bronze door following in 1958, replacing the wooden originals. This

Porta della Riconoscenza was commissioned in 1946 the thank the Virgin

for saving the city from German bombs during their retreat from Tuscany. The façade is a mixture of

sculpture, stained glass, mosaic and pinnacles, mostly depicting scenes

and figures from the life of the Virgin, including the life of her

parents, Joachim and Anna.

The 14 statues of the the pagan sibyls,

philosophers and

prophets who foretold Christ's coming, on the second tier were carved by

Giovanni Pisano. Those on the façade are copies from 1869, by Manetti, the originals being now

in the Museo dell'Opera, except for one, the bust of the figure of the

prophet Haggai, discovered in 1963, which is in the V&A museum in London.

The bas reliefs over the door, of 1297-1300, are by Tino di

Camaino, the Sienese sculptor who would carve the Petroni monument inside

the Duomo 15 years later. The 36 busts of the prophets and patriarchs

around the rose window are copies by Tito Sarocchi of the 14th century

originals.

The lantern on the dome dates to the 17th century

and is by Bernini.

When the old archiepiscopal palace was demolished in the mid-17th

century it exposed the nave wall on that side which therefore needed

cladding, in a gothic pastiche style, by Gianlorenzo Bernini.

The interior

Gothic, essentially in its

vaulting and looming quality, and somewhat overwhelming when you first

enter, due to the stripes and there being decorated surfaces all over.

Also the crowds and the roped-off areas guiding your route.

Somewhat generic stucco busts of Popes stare down from a frieze bellow the clerestory

all round the church. The gallery of 172 terracotta popes is where the original wooden

roof sat - the clerestory level being a later, more gothic, addition.

These popes originally included Pope Joan, a mythical figure, but it was

removed around 1600 on the orders of Clement VIII.

A set of Twelve Apostles

by Giovanni

Pisano adorned columns inside. In the 18th-century works by

Giuseppe Mazzuoli replaced the originals (now in the Opera Museum). The

black and white postcard (see below)

shows these 18th-century Apostles

in situ. These

replacements were themselves replaced by reproductions of the originals

and acquired in 1895 by the Brompton Oratory in London, where they remain.

The reproduction of the Pisano studio's originals are now to be found

outside on the roof of the nave and right-hand aisle.

Left side

The first three paintings over the altars on the left can safely be skipped,

as can much of the late 16th/early 17th century painting in here.

The fourth is the standout pale monumental marble Piccolomini

Altar (see right) commissioned in 1491 by

Cardinal Francesco Piccolomini from Lombard sculptor Andrea Bregno. The

statues of Saints Gregory and Paul in the two main niches to the right and

Saints Pius and Peter in the niches to left are by Michelangelo, who also

started the Saint Francis in the upper left niche, finished by Pietro Torrigiani. (Torrigiani it was, according to Vasari, who busted

Michelangelo's nose during a fight in the Brancacci chapel, was banished

from Florence, and ended up in England, working for Henrys VII and VIII,

among others.) Michelangelo's somewhat lacklustre work dates to 1501/3 and

is one of three projects, between the Pieta in Rome and the

David in Florence, which he left unfinished - he was commissioned to

carve fifteen figures here. The

sculpted Virgin

in the central upper niche is by Jacopo della Quercia. The small sweet

gold-framed Virgin and Child (1390) painting in the centre is

by Paolo di Giovanni Fei and is presumably a copy of the one in the Opera

museum. Its wooden frame has traces of sixteen compartments for relics.

Further on Pintoricchio's fresco of the Coronation of Pius III

as Pope is over the

carving-embellished entrance to the Piccolomini

Library

with cases containing open graduals and breviaries. The vivid and and

restored-looking ceiling and wall frescos, of c.1503, above

the cases are considered Pintoricchio's masterpiece, executed with the help of Giacomo Pacchiarotti. The library was made out of the old cathedral canonry for

donor Francesco Todeschini, who was Pope Pius III for 10 days, to honour,

and house the

Greek Latin and Hebrew codices of his mother's brother Aeneas Sylvius Piccolomini, who was

Pope Pius II and was a true, and

quite rare, Renaissance man amongst the Renaissance popes. Pintoricchio

had been a pupil of Perugino and brought a number of fellow pupils with

him, including Raphael. The latter's involvement in this cycle has been

contested since Vasari. There are lots of cartoons of the scenes by the

young Raphael, though. The cycle

begins at the rear to the right of the window and depicts ten incidents in

the life of Pius II and amounts to an oddly comprehensive program for

someone who was neither a saint nor a ruler. On display are the Duomo's

choir books, illustrated by Sano di Pietro, Girolamo di Cremona and Liberale di Verona amongst others.

Liberale's work is the most famous, including the striking miniature from

Gradual 12 showing the Allegory of the Wind with his big blue

hair. He came to Siena in 1466 from the fruitful scriptorium of

Santa Maria in Organo in Verona.

Around the corner past the Library is the domed Capella di San Giovanni

Battista, the work of Giovanni di Stefano, the son of the painter Sassetta,

finished in 1482 and created to house an arm relic of the saint donated by

Pope Pius II Piccolomini. The font (1484) and the bases of the decorated columns

are the work of Antonio Federighi, also responsible for part of the

pavement and the water stoups by the entrance. The bronze stature of

Saint

John the

Baptist in the gilt-decorated central niche is by Donatello, made in Florence in 1457 and

damaged in transit here. Dingy, damaged and restored frescoes by Pintoricchio and paintings by Giovanni di

Stefano.

The transept

Next is the crossing, two altars wide, and the famous pulpit by Nicola

Pisano, finished in 1268, after his Pisa Baptistery pulpit, with the help

of his son Giovanni and Arnolfo di Cambio. The panels, showing scenes from

the Life of Christ, duplicate those on the Pisa pulpit, but are deeper and

more detailed.

Carrying on, to the left of the presbytery is the corner Capella di

Sant'Ansano which has both the dark pavement tomb of Bishop Pecci of

Grossetto (1426-7) by Donatello (shifted to the left and tilted so as to

not be walked on) and the unrestrained wall tomb of Cardinal Riccardo

Petroni by Tino da Camaino of 1314/18. The latter is said to have been

influential on Italian tomb architecture for the next century and to have

had its scenes very influenced by those on Duccio's Maesta of just a year

previous.

To the right above it is a tall thin stained glass window

depicting full-length Saints Francis, Blaise and Anthony by

Domenico Ghirlandaio and his workshop. The altarpiece in here is the large Saint

Ansanus Baptises the People of Siena of 1593-96 (see right) by the Sienese mannerist

Francesco Vanni. It replaced

Simone Martini and Lippo Memmi's famous Annunciation, with Saints

Ansanus and Massima (see

The Altars of the Patron Saints

below right) presumably because that work was looking old fashioned.

It's replacing a Marian subject with an episode featuring the city's

obscure patron saint is also a reflection of its time.

The (usually closed) sacristy entrance is in the left wall of the

presbytery. It

contains a very damaged fresco cycle of the Life of the Virgin of

1411/12 by Benedetto di Bindo, one of the more major of the minor painters

that followed the Lorenzetti and Simone Martini. In the vaults of the

chapels here he also painted The Four Evangelists and The Four Doctors of

the Church. Also in here some fragments remain of frescoed scenes from the

lives of the four patron saints of Siena by Domenico di Bartolo, painted

c.1438.

The high altar of 1352 is by Baldassare Peruzzi, the Sienese architect

best known for collaborating with Raphael on the Palazzo Farnesina in Rome

for the Sienese banker Agostino Chigi. The stained glass in the large

round window is from a design by Duccio from 1288, making it very early

for such work in Italy. It's a copy, the original now being in the Museo

dell'Opera, and features a very early depiction of the Assumption.

The back of the presbytery has carved stalls with intarsia panels by Fra

Giovanni da Verona, famed also for his work in the church of

Santa Maria in Organo in his home city. The panels were originally in

the choir of the Abbey of Monteoliveto Maggiore but were brought here in

1813 and inserted into the backrests of the 14th-century stalls. The frescoes

above are mostly by Domenico Beccafumi and Ventura Salimbeni.

Right side

...was fenced off on my visit...

The right side has thinner pickings, but there's the Capella del

Sacramento nine chapels down opposite the Capella di Sant'Ansano. It has

five bas reliefs probably removed from a dismantled pulpit carved by

Domenico dei Cori in 1425.

Nearer the main door, mirroring the position of

the Capella di San Giovanni Battista opposite, is the Roman Baroque style Capella Chigi, built

in 1659/62 to a design by Gian Lorenzo Bernini for Alexander VII, Fabio

Chigi, a Sienese pope, it

was the last major addition the Duomo's fabric. It was intended to house

the venerated Madonna del Voto, an anonymous 13th-century painting

which has been attributed to Guido da Siena and, most recently, to

Dietisalvi di Speme. This image, cut down from a larger work, possibly a

dossal, previously

called the Madonna delle Grazie, is the one which tradition says is

the Virgin before which the pre-Montaperti dedication of Siena to the

Virgin was made. Two of the four

niche statues - the ones nearest the door - are by Bernini - the Mary

Magdalene and

Penitent Saint Jerome, as is the gilded bronze frame for the Virgin,

with its angels and putti, and the design of the railings.

The fifth altar, after four more skippable altars mirroring those opposite,

from the door on the right is the Tomb of Tommaso Piccolomini, above the

door to the campanile, by Neroccio di Bartolomeo Lando. Below are bas

reliefs depicting episodes from the life of the Virgin by Urbano da

Cortono, a collaborator with Donatello known for his Tomb of Cristoforo

Felice in San Francesco in Siena.

The pavement

Begins with geometric patterns and some

scenes outside and progresses to 56 figurative intarsia marble panels inside. Made between

1349 and 1547 and involving almost every artist who worked in the city

between these dates, preparing the cartoons that the stonemasons would

then make into coloured marble. The panels initially echoed the black and

white stripes of the walls, but by the time the biblical and civic

subjects in the

transept were being made the colouring had got richer, using red and

yellow too. New Testament subjects were avoided as it was thought

blasphemy to walk on Christ, his Mother, and the saints. By 1600 the floor

was being covered with boards to protect it from wear. Replacements and

repairs of worn panels followed, largely in the 19th century by sculptors

Leopoldo Maccari and Antonio Manetti.

Campanile

Built in 1313, it has six bells, the oldest one being cast in 1149.

It has a relief of the Virgin and Child of 1458 by Donatello over the door.

He had returned to Siena in 1457 hoping to be asked to make the bronze

doors, but was disappointed.

Lost art

in the Museo dell'Opera del Duomo

The Museo here has rooms of stuff, mostly from the Duomo,

and was created in the 19th century by walling up the first three arches

of the right-hand aisle of what was planned as the new huge cathedral in

the 14th century. Here much of the statuary, replaced by copies in the

19th century, can be seen up close, and Duccio's stained-glass window for

the choir.

Concentrating on altarpieces...

The early 13th century Madonna degli Occhi Brossi (Madonna with the

Big Eyes) is one of the earliest altarpieces to have

survived. It is, in fact, most likely that it was created as an

antependium

(altar frontal) as it has been cut down, losing flanking narrative scenes.

It was probably moved up onto the high altar in the Duomo during the 13th

century. The central Christ child and the Virgin's pose places it firmly

in the Byzantine Hodegetria tradition. It is believed that this was the

Virgin that was addressed during the dedication of Siena to the Virgin in

1260 on the day before the famous victory of the Sienese over Florence at

the battle of Montaperti at which she ensured the Sienese victory with a

divine fog..

Pietro Lorenzetti's late and lovely Birth of the

Virgin of 1342 (now in the same room as Duccio's

Maesta in the Museo dell'Opera) was the central panel of the Saint

Savinus Altarpiece over the

altar dedicated to the saint (one of Siena's four patron saints) in the corner chapel of the left transept.

(See

The Altars of the Patron Saints

right.) The side panels, Saints Savinus and Bartholomew, are lost

but a

predella panel showing Saint Savinus before the Governor Venustianus in the National

Gallery in London.

The four panels depicting Saints Catherine of Alexandria, Benedict,

Francis of Assisi and Mary Magdalene by Ambrogio Lorenzetti of

1320/30, which used to flank a, now lost, central panel, were originally on

the altar of the Magi in the Duomo. These panels underwent restoration in

1997. Also by Ambrogio is the special

Presentation in the

Temple which used to be in the San Crescenzio

chapel here, now in the Uffizi. It was painted in 1342, the same year as

his brother's Birth of the Virgin mentioned above.

A favourite polyptych of mine, The Virgin of

Humility with Saints Augustine, John the Baptist, Peter and Paul by

Gregorio di Cecco, a pupil and adopted son of Taddeo di Bartolo, signed

and dated 1432 (see above and a sweet detail right) taken from the Altar of the

Visitation here. A pinnacle panel of The Annunciate Angel is in a

private collection in Turin.

The Virgin and Child Enthroned with Saints John the Evangelist,

Nicholas, Gregory and Jerome, a late altarpiece (1480) by Matteo di Giovanni

for the chapel of Niccolò Cristoforo Celsi in the Duomo. And by the same

artist, a altarpiece of the Virgin and Child Enthroned with Saints Anthony

of Padua

and Bernardino and Angels, from the altar of Saint Anthony of Padua

chapel in the

Baptistery.

A series of panels which

made up a reliquary cupboard by Benedetto di Bindo, who also decorated the

sacristy here, and trained Sassetta.

Lost art

not in the Museo dell'Opera

The anonymous Blessing Redeemer altar frontal in the Pinacoteca has

been dated to 1215 and linked with the

Madonna degli Occhi Grossi mentioned above, being in the original format of that work

before it was cut down.

A section of marble choir

screen by the workshop of Nicola Pisano c.1272 is in the V&A in London.

It has a female head is one rectangle and a lion and cub in another.

The coloured marble design on its reverse suggests that it was later used

as a table top.

A 1342 altarpiece of the Presentation of the Virgin, a

fine late work by Ambrogio Lorenzetti, is in the Uffizi. A panel of the

Allegory of Redemption, also by Ambrogio, is in the Pinacoteca. It's

thought that they were originally once part of an altarpiece for an altar

dedicated to Saint Crescentius here. (See

The Altars of the Patron Saints

right.)

They both ended up in the Spedale di

Monna Agnese (see

San Niccolò in Sasso ) from which they

were later dispersed, The Presentation going to the Florence

Accademia in 1822. It is now in

the Uffizi. A pinnacle by Ambrogio depicting Saint John the Baptist

is in Copenhagen.

The Adoration of the Shepherds by Bartolommeo Bulgarini in the Fogg

Museum, dated c.1350, is now thought to be the central panel of the

altarpiece in the chapel of Saint Victor (See

The Altars of the Patron Saints

right.)

A pair of panels (sometimes previously

attributed to the Palazzo Venezia Master) of Saints Victor and Corona, now in Copenhagen, are thought

to have been parts of the same altarpiece, along with two predella panels,

now in the Städel in Frankfurt (The Blinding of St Victor) and the

Louvre ( The Crucifixion), all now thought to be by Bulgarini.

The Presentation of the Virgin in the Temple altarpiece by Paolo di

Giovanni Fei of 1398-1399, was commissioned for the chapel of San Pietro

here, is now in the National Gallery in Washington.

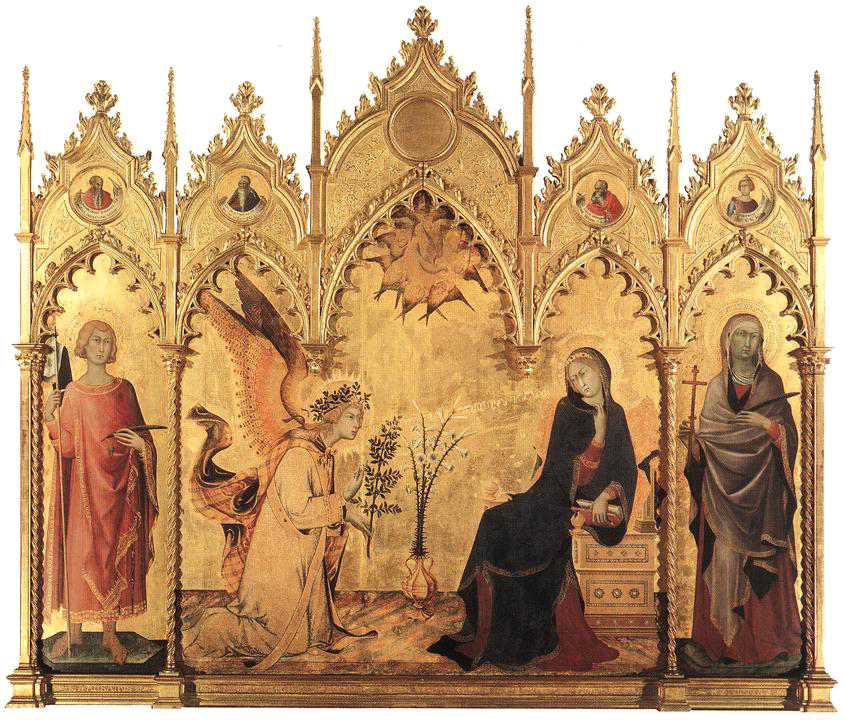

The exceptional Annunciation with Saints

Ansanus and Massima (see right) was painted in 1333 by Simone Martini and Lippo Memmi, his

brother-in-law, for the altar of Saint Ansanus here, located to the left

of the chancel, where Saint Ansanus Baptising the Sienese

from 1593-96 by

Francesco Vanni is to be seen now. The Annunciation, one of

a set of four altarpieces dedicated to Siena's patron saints

(See

The Altars of the Patron Saints

right.) was moved to

the church of

Sant’Ansano towards the end of the 16th century

having been replaced by the Vanni presumably because it was

looking old fashioned. It is now in the

Uffizi, where it went in 1799 in a poor exchange for two paintings by Luca

Giordano, Christ Before Pilate and The Deposition, both from

1682. The rarely-depicted figure of Saint Massima, Ansanus's god-mother, was previously

thought to be Saint Margaret.

The first

documented commission awarded to Vecchietta is dated 1439 and is for two

statues,

The Virgin and

the Annunciate Angel which he sculpted and painted, along with Sano

di Pietro, for the high altar here. They are now lost.

The Madonna della Neve (Virgin of the Snow)

altarpiece of 1432, painted for the Saint Boniface chapel here by Sassetta

is now in the Uffizi. It was commissioned by Lodovicha Bertini, the wife

of the sculptor Turino di Matteo. She chose the saints depicted and the

subject of the predella panels - the miraculous fall of snow on the 5th of

August 852 that prompted the building of Santa Maria Maggiore in Rome. It is an early forerunner of the

unified-space altarpiece - the gothic gables above the figures still

divide the space into three.

Nineteen illusionistic intarsia panels for the choir stalls in the

Saint John Chapel here were made by by Antonio Barli in the late 15th

century. Those that were moved to the Collegiata of San Quirico d'Orcia in

1749 have survived, the rest have been lost.

The church in art

Domenico Beccafumi's The Offering of the

Keys of the City to the Virgin before the Battle of Porta Camollia, a

panel of 1526/7, is painted taking place in front of the chapel dedicated

to the Madonna delle Grazi, which housed the famous votive image,

before the chapel was demolished in 1659. It is now in Chatsworth House in

Derbyshire. An earlier Offering of the Keys, from 1483, when exiles

from the Novesco threatened to capture Siena, was commemorated in a

Gabella panel by Pietro Orioli which also shows the chapel, more clearly.

It is still in the Siena State Archives.

|

|

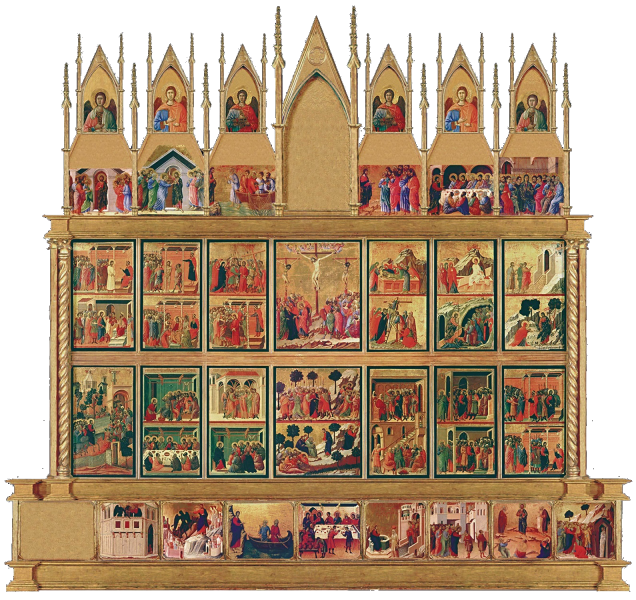

The Maestà

The Maestà by Duccio was painted between 1308 (the contract

survives) and

1311, when it was processed at noon on the 9th of June with great crowds

and ceremony through Siena. It was unique, huge and double-sided, and part

of the ambitious plans for the expansion of the Duomo. Its display is now spread around

three walls of one room in the Museo dell'Opera - the main panel on one

wall and the spandrel and pinnacles panels on the other two - which I found functional

but dull. It is said to have originally had a

complicated carpentry mechanism involving curtains, a canopy and three painted

wooden angels who descended to hand the priest the Host, chalice and

corporal (linen cloth); with four more angels holding candles (two in

front, two behind) five more candlesticks and two ostrich eggs.

The front main panel (see above) shows the Virgin as the Queen of Heaven enthroned and

surrounded by angels and saints, with the four patron saints of Siena

kneeling. These are, on the left Ansanus and Savinus, two martyred

bishops, and on the right Crescentius, a child martyr under Diocletian

whose relics came to Siena Cathedral in 1058, and Victor, a Syrian soldier

who was declared a patron of the city after 1288, replacing Saint

Bartholomew as one of the four. The ten apostles

not in the main panel group are half-length in a freeze in the top

corners. Episodes from the life of the Virgin (also readable as the early

life of Christ) are depicted in the predella, with events from her last

days on the lower pinnacle panels. The bottom row begins with the The

Annunciation, the top row with the The Annunciation of the Death of

the Virgin. The narrative scenes in the predella alternate with

prophets with scrolls.

The front faced the nave, with the back visible to the canons in the choir.

The back

(see below) depicts scenes from the life of Christ - his ministry in the predella,

his passion on the main register and his post-resurrection appearances above.

Angels top the pinnacles on both sides.

It has been much moved and chopped about over the centuries. It was

on the high altar for nearly two hundred years, but in 1506 a new

altar was built and it was replaced by Vecchietta's bronze

tabernacle (taken from the high altar of the church of

Santissima

Annunziata in Santa Maria della Scala). It was documented as

being above the Saint Sebastian altar in

the left transept in 1536. In 1776 it was cut into seven pieces and was sawn in half

front-from-back, incompetently - the Virgin's face was damaged. The front was

placed in the Saint Ansanus chapel in the left transept and the back put

in the Saint Victor chapel, with the predella and top panels put in the

sacristy. In 1878 it was put back together and put in the Museo dell'Opera.

Major restoration work was carried out in 1956. The missing predella panels, which were put on the market in the

19th century, are now (one each from the front) in the National Galleries

in London and Washington; with rear predella panels now in the Frick, the

National Galleries in London (which has two) and Washington, the Thyssen Bornemisza in

Madrid and

the Kimbell in Texas. Pinnacle angels are now in Brussels, Philadelphia,

Massachusetts and 's-Heerenberg in The Netherlands. The Coronation of

the Virgin is in the Szépmüveszéti Muzeum in Budapest.

The lost large central upper panels would probably have been The

Assumption of the Virgin and The Coronation of the Virgin on

the front and The Ascension and Christ in Glory on the back.

The lost first predella panel on the back would probably have been The

Baptism of Christ or maybe the first of his temptations, as it's

followed by the second and third.

The Altars of the Patron Saints

By the 13th-century the patron saints of Siena were

Ansanus, Sabinus, Victor and Crescentius, they being shown

kneeling before the Virgin in Duccio's Maesta. Amongst these

obscure saints' claims to worthiness were Sabinus being believed to be

the first bishop of Siena, Crescentius simply because the bishop had

acquired his relics in 1058. A later, and equally nondescript, substitution

was Saint Victor,

who had replaced Bartholomew.

Victor was a soldier in 2nd century Syria

martyred for his conversion to Christianity. His name is linked in

martyrdom with Saint Corona a 16 year old also martyred, for sticking up

for him. She became better known during the recent Coronavirus

pandemic.

Crescentius had been beheaded in Rome, and Antifredus, the Bishop of

Siena, acquiring his relics from Rome is the only known scene from his

'life' in Sienese art. As an early Christian martyr he was a good choice.

Savinus was venerated as the first Bishop of Siena, despite his actually

having been Bishop of Faenza. Both saints are evidence of Siena's somewhat

desperate need for an ancient past, given that the city had only really

gained stature in the medieval period. Ansanus was a better bet. A

3rd-century Roman persecuted during the reign of Diocletian, he had

been an impressive converter and baptiser of heathens after being brought

to Siena as a prisoner, beheaded between

Siena and Arezzo in 303. His body is said to have been found by a

shepherdess in 1107, and his head was snatched from the also-claiming

Bishop of Arezzo and brought back to Siena in procession. The crowd's

cries of il Santo viene ('the saint is coming') led to the Porta

Pispin formerly being known as the Porta San Viene. It is said that he is

Siena's John the Baptist, as his baptising arm was processed through the

city on the Tuesday after Penetecost, one of his three observed feast

days. This unimpressive bunch explains why the population of Siena later

took Catherine and Bernardino so much more to their hearts.

As part of the ambitious plans of the early

1300s to expand the choir and add a new sacristy, it was decided to commission altarpieces for the

new altars either side of the high altar devoted to each of

them and, unsurprisingly, to feasts of the Virgin. These were to be

commissioned from the outstanding successors of Duccio who may or may not,

have been members of his studio.

Firstly, in 1333, came the one for Saint Ansanus

-

Simone Martini's famous Annunciation, with Saints Ansano and Massima,

painted with Lippo Memmi, his brother-in-law, signed by both of them

and dated. The division of labour between the pair is uncertain and has

been much debated. It's the only one of the

three with a gold ground, but its depth and illusionistic detail are

impressive and innovative. The female saint previously thought to be

Margaret is now thought to be Massima, a martyr and the god-mother of Ansano. There would have been a predella, now

lost, showing scenes from the life of the saint, and the central tondo of

God the Father is also gone.

Ambrogio Lorenzetti's Presentation

in the Temple was next, for the altar of Saint Crescentius, followed

by his brother Pietro's Birth of the Virgin, both in 1342, nine

years after Simone's altarpiece, he having left for Avignon. They share

the importance of being the first narrative scenes made the central panels

in an altarpiece. They have also both lost their flanking saint panels,

confirmed as present in early inventories and said

to have included the dedicatory saints, and their predellas.

The Birth of the Virgin was flanked by Saints Sabinus and Bartholomew,

the latter being Siena's favoured apostle. Documents detailing the payment

of a scholar for translating the story of the life of the saints have led

to the belief that the altarpiece had a predella with such scenes. The

only likely panel found is in the National Gallery in London. It's

unobvious subject has been identified as Saint Sabinus before the

Roman Governor of Tuscany.

The Presentation at the Temple is a scene closely associated with

the feast of the Purification of the Virgin. Ambrogio's panel is known to

have been flanked by panels showing Crescentius on the left, carrying his

head (cephalophorous is the term for this), with the Archangel

Michael on the right. It has been suggested that the Allegory of

the Redemption in the Pinacoteca could have been part of the predella.

The central panel of the altarpiece painted for the altar of Saint Victor

was lost, but it was documented as a Nativity. The 20th century saw this identified as the Adoration of the Shepherds

by Bartolommeo Bulgarini in the Fogg Museum, which has been much cut down,

dated c.1350 (see right). A pair of panels of Saints Victor and Corona, now in Copenhagen, are thought to have

been parts of the same altarpiece, along with two predella panels, in

Frankfurt and Paris. (See

Lost art

not in the Museo dell'Opera

left.)

|